Places to visit in Bilbao

Bilbao – Old Town Memory Walk

This walk is not just a stroll through the old streets of Bilbao — it’s a walk through the city’s memory. Everything here lies close together: the Gothic gates of Santiago Cathedral, the soft murmur of the “Dog Fountain,” the old plaques still marked by the great flood of 1983, and Bar Xukela, where the spirit of the city lives in a glass of wine and laughter at the counter.

We follow Calle del Perro and Calle de la Torre — streets whose names hold legends and the echoes of ancient family towers. At every turn, a story appears: about the Basques, whose defensive towers once stood like the stone houses of Svaneti; about Diego María Gardoki, the first Basque to serve as Spain’s ambassador to the United States; about Pedro Arrupe, the Basque priest who renewed the Jesuit order in the twentieth century.

Our path leads to the river where ships once lined the shore, and finally to El Arenal — the park where Bilbao learned to breathe, to love, and to listen to the quiet rhythm of its own heart.

This walk is like a simple, honest conversation with the city — no guide, no performance, just a friend who has a story waiting behind every corner.

Paseo del Arenal is one of the most pleasant places to begin a walk through Bilbao. From the convenient parking area beside the park, it’s only a few steps to the riverbank. Here, right at the water’s edge, the city opens in a calm panorama: palm trees, long rows of plane trees, benches in the shade, and the quiet surface of the estuary where the reflections of bridges and buildings drift slowly by.

Once, this was a sandy shore and a natural shipyard. Boats and barges were launched here by the people of Bilbao. In the late eighteenth century the area was redesigned — paths, ponds, and lanterns appeared — and Arenal became the city’s main promenade, though it kept the name of the old sandy beach.

Today, the atmosphere still carries the gentle rhythm of old Bilbao: locals walking their dogs, teenagers on skateboards, tourists sitting with a coffee and watching the river. Walking toward Arenal Bridge, it’s worth pausing at the bronze fountains decorated with sea creatures — a rare example of late-nineteenth-century urban sculpture.

The bridge, built in the 1930s, links the old town with the new and offers one of the best views of Santiago Cathedral and the rooftops of Casco Viejo. The riverside path is especially beautiful in the morning or evening, when the light falls at an angle and the air fills with the smell of wet stone and nearby cafés. The path is smooth and easy to walk; for photos, the best spot is a little farther from the bridge, where the river, the trees, and the soft line of the city appear together in the water’s reflection.

The Arriaga Theater stands right beside the water on Arenal Square, like a guardian at the entrance to the old town. Its façade immediately draws the eye: pale stone, soft curves, domes, and sculptural details give it the elegance of a Paris opera house set on Basque soil. Built in the late nineteenth century by architect Joaquín Rucoba, it became one of the first major symbols of Bilbao’s cultural awakening at a time when the city was quickly shifting from a port to a rising European bourgeois center.

The theater is named after Juan Crisóstomo de Arriaga — a composer who died at twenty and is often called the “Basque Mozart.” His music opened the theater’s very first performance, and since then Arriaga has remained the heart of Bilbao’s performing arts.

The building has lived through more than one disaster. In 1914 it burned almost completely, and in 1983 it was flooded during the devastating river surge. Each time it rose again, reopening its doors — much like the city itself, stubbornly returning to life.

Today the Arriaga Theater is both an architectural highlight and an important point on the walking route: it marks the transition from the riverbank to the narrow streets of old Bilbao. During the day the square is lively, but in the evening, when the lights come on and the domes shimmer in the river’s reflection, the façade looks like part of a grand stage set — with the city playing the leading role.

The Church of San Nicolás stands right at the water’s edge, on the spot where all routes once met — river, land, and trade paths. Long before Bilbao became a city, this was a shallow crossing and a small riverside dock where caravans from Castile arrived with wool. Archaeologists have found traces of twelfth- and thirteenth-century warehouses and walls beneath the church — a reminder of a settlement that existed here centuries before Bilbao was officially founded.

In 1300, Diego López de Haro, lord of Biscay, granted the charter that created the villa of Bilbao, and this place became its center. Fortifications were built here, followed by the first city walls. Later, in 1334, King Alfonso XI ordered the construction of defensive towers and an alcázar on this site — part of their foundations now lies under the present church.

The first Gothic church rose in the fifteenth century and was consecrated in 1433. It was modest, with a single nave, but as the town expanded, the church was rebuilt. By 1510 it had taken a form close to what we see today. Over time, a Renaissance portal was added, and in the eighteenth century, a Baroque tower appeared. The architecture became a blend of eras: Gothic austerity, Renaissance balance, and Baroque decoration.

San Nicolás stands by the estuary for a reason — this was the point of control over the crossing and the trade route. The view of the church with the bridge became one of the symbols of the city and even entered Bilbao’s coat of arms. The front balcony once served as a ceremonial platform for city officials, who watched festivals and public events from above. Inside, beneath the floor, you can still see archaeological remains of old fortifications and a medieval cemetery, whose gravestones later became part of the stone pavement.

This is more than a church — it is the place where Bilbao was born and from which it grew. Here you can feel the shift from a medieval settlement to a port city that eventually became Castile’s gateway to the Atlantic.

On Saint Nicholas Square, across from the old Baroque church, a small plaque recalls a visitor who passed through long before Bilbao became the modern city it is today. In 1780, John Adams — the future president of the United States, then a diplomat traveling to France — arrived in this port. He spent a night at a local inn and later wrote about how deeply the Basque way of life impressed him.

The Basque Country has always stood apart. Caught between sea and mountains, between Spain and France, it preserved its own laws — the fueros, local rights that granted more autonomy than most Europeans knew at the time. The Basques were sailors, fishermen, and traders, people whose lives depended on tides and wind, yet they were also stubborn defenders of self-rule. It was this mix — openness to the sea and a fierce sense of independence — that struck Adams most.

Here he encountered a society where tradition did not limit freedom, and local rights lived comfortably within a larger political structure. Years later, back in America, these observations echoed in his thinking about federalism — the balance between the independence of individual states and the unity of the nation.

Today the Church of Saint Nicholas, patron of sailors and travelers, stands beside the place where Adams once stayed. Its façade faces the river as if reminding us that the sea carries more than ships and goods — it carries ideas. And sometimes those ideas become the wind that changes history.

Pintxos are often the first doorway into Basque food culture. The word comes from the Spanish pinchar — “to pierce” — a reminder of the wooden skewer that once held a simple bite together: a piece of bread topped with ham, an anchovy, or an olive. What began as a practical way to keep ingredients from sliding apart eventually grew into an entire culinary tradition. The bites became more varied, the presentation more refined, but the skewer remained — a small symbol of where it all started.

Plaza Nueva is one of the best places to experience this tradition. Under its stone arcades sit old bars where each chef creates their own version of the classics — salted cod, seafood, tiny omelets, bold sauces. In the evenings, people drift from one bar to the next in a rhythm known as txikiteo. It’s quick, lively, friendly — a perfect reflection of the Basque way of socializing.

The square itself was built in the mid-nineteenth century as a sign of a new urban era, bringing government offices, commerce, and everyday life together in one open space. On Sundays, its antique market keeps the old spirit alive. Among the stalls you’ll find seashells remembering Bilbao’s maritime past and the Camino de Santiago, whose shell symbol marks the route through Biscay. And mixed with the antiques are objects from fishermen’s homes, traders’ shops, and craftsmen’s workshops — small fragments of a time when the city lived by the sea and the marketplace.

Plaza Nueva gathers everything Bilbao has always been: shaped by the ocean, loyal to its traditions, and in love with simple things done well — like a pintxo you really have to taste to understand why it became the emblem of an entire culture.

When you pick up old cufflinks or a carved pipe stand, it feels as if you’re holding a small fragment of a world that has disappeared. They once belonged to a culture of precision and dignity — objects that signaled status, taste, and a certain discipline of life. Cufflinks first appeared in seventeenth-century France and, by the nineteenth century, had become an essential part of a gentleman’s wardrobe. Their material and design revealed a lot about a man — his wealth, his habits, even his character. Their golden age came in the first half of the twentieth century, when they expressed confidence and professional success. Then shirts with buttons took over, and cufflinks almost vanished.

In Bilbao, these items became popular during the same period when the city was evolving from a port into one of Spain’s major industrial centers. Shipyards, steel factories, banks — all of it created a new class of engineers, businessmen, and financiers. Their offices displayed pipe stands; their cuffs shone with metal links; their walls carried maps of trade routes. These objects represented a belief in order, discipline, and progress — the values of a rising bourgeois Bilbao convinced of its future.

But alongside this elegance grew a quiet sense of distance. For workers and ordinary Basques, such objects didn’t represent refinement; they reminded people of a world that was not theirs. As Madrid tightened control and reduced Basque autonomy, the city’s economic success looked less like prosperity and more like a polished façade hiding cultural pressure. So in the 1930s, when the independence movement gained strength, the struggle was not only about land and language — it was also against that bourgeois lifestyle, where style seemed to replace freedom.

After the Franco era, most of that world faded. What survived now rests on market tables, like those in Plaza Nueva. Among seashells, wooden figures, and old books lie cufflinks and pipe stands — no longer symbols of power, only reminders. And in a way, that feels fair: objects that once divided people have become part of a shared past. Today they are simply things, markers of a time when even luxury could be a kind of protest, and simplicity a quiet form of dignity.

The Sunday antique market on Plaza Nueva reveals more than a love of old objects — it shows a particular Spanish way of treating memory, handwriting, and the written word. On the tables you find old pens, decks of cards, books — everyday things through which people once expressed themselves and left a trace of who they were.

Spanish writing culture has never been about formality; it’s about feeling. Here, people continued writing letters by hand long after the rest of Europe moved on. They cared about paper, ink, and even the rhythm of their handwriting. A good fountain pen wasn’t just a tool — it was an extension of thought.

The books you find here are not random either. Many are novels and personal stories, focused on people and cities, where the inner world matters more than appearances. Spaniards read emotionally, almost as if they’re in conversation with the author — not as a task or a duty, but as a shared experience. That’s why each volume feels less like merchandise and more like someone’s memory placed gently on a table.

And this reveals a cultural difference. In England, writing, reading, and book collecting often reflect a tradition of order, intellect, and archival thinking — knowledge arranged into structure. In Spain, these same acts are tied to life itself. People write to express, read to feel, and save things so that emotion isn’t lost.

So the old pens and books at the market are more than antiques — they are signs of a deeply personal relationship with words. Spaniards turn writing into a continuation of human warmth, and perhaps that’s why their culture feels so alive even in objects that have long fallen out of everyday use.

The Plaza Nueva in Bilbao carries the shape of Spanish order—an imperial idea of symmetry, arches, and neoclassical façades placed onto Basque soil. Its geometry echoes Madrid’s Plaza Mayor, as if the empire tried to anchor its own vision of harmony and authority here. This kind of architecture once served as a declaration: the layout of a square was meant to express stability, law, and the certainty of a system where a royal signature sounded absolute—“Yo, el Rey.”

But time has a way of shifting meaning. Even Charles V, the ruler who once held half the world, eventually stepped away from power, retired to a monastery, and lived quietly among books, a cat, and a canary. That small bird—fragile, bright, and domestic—outlived kings and became a symbol of calm and inner balance in Spanish culture. Later, canaries spread across Europe, and by the nineteenth century even Russia considered a caged canary a mark of a respectable home—a symbol of comfort and of controlling a small world when the larger one felt unstable.

The Basques adopted the architecture but not the obedience built into it. On this same square you hear canaries, but also the smell of roasted peppers and anchovies. Every evening people gather with a glass of wine and a plate of pintxos—food that is proudly, stubbornly their own. Spain brought the form; the Basques filled it with their voice. And if the canary sings behind its bars, the Basque spirit sings in freedom—through its language, traditions, flavors, and the rhythm of this land.

Vinyl records at the Sunday market on Plaza Nueva are more than music — they’re a living piece of the city’s memory. Back when Bilbao was booming as an industrial powerhouse, almost every home had a record player, and the warm crackle of vinyl meant comfort, modernity, and a small window to the wider world. Records were sold in music shops under these very arcades, and in the same buildings where collectors now flip through covers they first saw as teenagers.

Vinyl reached Spain in the 1950s, but it was the 1970s that shaped a whole generation through sound. Here in the north, radios picked up not only Madrid but also France, and young people mixed Beatles, Bowie, and Basque Rock into a new musical identity — global and local at once, rebellious and poetic. That mix still defines the way Bilbao hears itself.

Today these records aren’t just items for sale; they’re artifacts of a time when music was carved into physical grooves — warm, imperfect, alive. And like everything in Bilbao, vinyl also carries the city’s spirit of resistance. During the years of censorship, songs in Basque played quietly in bars and living rooms — soft, but stubborn. It was freedom set to melody, something no government could silence.

So now, among old books and between Disney albums and records by Miguel Bosé, you find discs from local 1970s bands. It’s not nostalgia — it’s continuity. Under the stone columns of Plaza Nueva, the sound of vinyl brings back a time when every song was an event, not background noise. A time when people listened to music the way they spoke with one another — attentively, thoughtfully, with their whole heart.

Bilbao, the glass-fronted balconies called miradores changed the way the city looked and lived. They appeared at the end of the nineteenth century, when people began looking for a way to brighten their homes and steal a little more daylight from the often grey Basque sky. Instead of stepping outside, residents pushed their homes outward — building small wooden and metal structures that floated off the façade and wrapped them entirely in glass.

What started as a practical solution soon shaped the city’s personality. Miradores created a new rhythm along the streets: rows of glowing boxes, each one half-room, half-lookout. From inside, people could watch the neighborhood breathe — children running below, voices drifting up from cafés, the slow shift of weather over the hills — all while remaining part of the scene.

They turned façades into something alive, connecting indoors and outdoors in a way that feels very Bilbao: a city where private life is never completely separated from the street, and where architecture grows from human habits, not from grand theories.

Miguel de Unamuno Square is one of those places where the history of Bilbao doesn’t just surround you — it presses up from the ground itself. From here the old Mallona steps begin their climb toward the Basilica of Begoña, a shrine the city treats as the quiet center of its spiritual life. But the square honors a different kind of devotion: the life and questions of Miguel de Unamuno, the writer and philosopher born in Bilbao, a man who spent his whole life trying to reconcile things that resisted reconciliation — reason and faith, Spain and the Basque Country, logic and the human heart.

For years his bronze bust, sculpted by Victorio Macho, sat forgotten in the basement of city hall. Now it looks out over the square again, as if Unamuno is still asking his lifelong question: What does it mean to be Spanish, Basque, human?

The fountain here is called the “Source of the Four Elements” — earth, water, air, fire. It’s more than decoration; it holds the kind of symbolic harmony Unamuno searched for. Each jet feels like an answer to him: life is a balance of opposites, and everything holds together only when tension becomes unity.

Casco Viejo, the old quarter that surrounds the square, is the birthplace of Bilbao. Centuries ago this was a cluster of fishermen’s houses and river warehouses along the Nervión estuary. As the town grew, these muddy paths became busy market streets, eventually forming the famous seven parallel lanes — Zazpikaleak, the “Seven Streets.” Today they’re pedestrian and full of cafés, shops, morning coffee aromas, but beneath all the bustle you can still hear older rhythms — the river’s murmur, the market’s hum, the echo of ships calling out to one another.

But this square is more than charm and heritage. In the nineteenth century, this part of the Basque Country was the beating heart of the Carlist Wars. Supporters of Don Carlos fought against liberal Spain to preserve monarchy, Catholic tradition, and the Basque historic rights known as fueros. For the Basques, it wasn’t just a fight over succession — it was a struggle for their identity, their language, their way of life. Bilbao stood with the new world; the villages around defended the old. When the Carlists lost, the Basque Country lost parts of its autonomy — but not its stubborn sense of self. That spirit is still here: in the language spoken on the streets, in the culture, in the quiet resolve of its people.

On this same square stands the Basque Museum — Museo Vasco. Its galleries gather the region’s memory: tools, weapons, clothing, maps, objects from daily life. Among them are documents from those wars, reminders of the storms that passed through this city. And when you stand by the fountain and look around, it’s clear that these are not just stones and bronze. This square holds the memory of a place that knows how to argue, endure, and — no matter what happens — remember who it is.

The Euskal Museoa — Bilbao’s Basque Museum — stands just off Miguel de Unamuno Square, inside a building that has lived many lives. Once a Jesuit college and monastery dedicated to Saint Andrew, it was built in the seventeenth century on the footprint of older homes, then expanded and altered over the centuries. Because of that, its façade reads like a timeline carved in stone.

At street level, around the portal, you see neat blocks of carved sandstone — the orderly square masonry typical of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the era of monasteries and Baroque architecture. It gives the front of the building a sense of weight and quiet authority.

Higher up and along the sides, the stone changes completely: rough, uneven walls made of unshaped rocks and river boulders held together with lime mortar. These are the survival marks of earlier structures — pieces of medieval walls or old service buildings from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that were simply woven into the later monastery.

The museum sits inside all these layers at once, carrying the history of Bilbao’s most ancient quarter in its own walls long before you step through the door.

Walking through old Bilbao and turning onto Calle de la Cruz, you feel the city’s early heartbeat. This was one of the original seven streets — the narrow beginnings from which Bilbao grew. A stone cross once stood here, giving the street its name. For travelers it was a sign of protection; for the townspeople, a marker of faith and guardianship. The plaques on the walls still tell that story: how in the thirteenth century the city rose from seven cramped lanes, how wooden houses burned again and again, and how in the nineteenth century Bilbao rebuilt itself into the place we see today, with its squares like Plaza Nueva and San Francisco.

On this street stands the Church of San Juanes, one of the oldest in the city, built in 1622. Its strict, almost stern façade — a blend of classical lines and Baroque gravity — matches the Basque character well: no excess, just stone, time, and dignity. The church once belonged to the Jesuits, the order founded by Saint Ignatius of Loyola — the Basque whose name became a symbol of scholarship and spiritual resolve.

Everything changed in 1767, when King Charles III, a monarch shaped by Enlightenment ideas, expelled the Jesuits from Spain. They were respected, but also feared — too educated, too independent, too capable of shaping minds and politics. Their property was seized, their schools and churches handed over to the city. San Juanes lost its Jesuit identity and became the parish church of the Two Johns.

That story mirrors the evolution of Bilbao itself. A town born of faith and craftsmanship gradually became a city of commerce, industry, banks, and theaters. Places once dedicated to theology now teach economics and art. And standing before the walls of this church, you realize: Bilbao knows how to change, but it never forgets those who helped it grow.

Calle Tendería is one of those streets where old Bilbao rises up from the stones under your feet. It belongs to the original “Seven Streets” — Zazpikaleak — the narrow lanes where the city first took shape. Its name comes from tenderos, the shopkeepers and craftsmen who once filled this area. In medieval times the street was a tight, noisy strip: workshops on the ground floors, flats above them, fabrics hanging from windows, and the air thick with the smells of bread, leather, and sea salt. You could buy anything here — candles, spices, tools — and with every purchase came a whisper of news from ships arriving from faraway ports.

But Tendería has another layer, quieter and almost spiritual. One of the routes of the Camino de Santiago passed through this street on its way west. A scallop shell set into the pavement and a wooden figure of a pilgrim near the entrance still remind visitors of that ancient movement of people — tired, hopeful, walking toward something greater than themselves.

The story of Saint James, whose shrine the Camino leads to, goes back to the earliest days of Christian Europe. After the death of Christ, James traveled to the far reaches of Iberia to preach. Returning to Jerusalem, he was martyred, and according to legend, his followers placed his body in a boat without oars. Guided only by divine will, it drifted all the way to Galicia. Seven centuries later, a cluster of shining lights appeared above his forgotten grave — a sign that revealed the place that would become Santiago de Compostela, the “field of the star.”

When the boat reached the shore, the apostle’s body was said to be covered in scallop shells. Since then, the vieira has become the symbol of the saint and of the journey. And the meaning runs deeper: the grooves of the shell converge at one point, like the roads of Europe leading toward a single purpose — clarity, renewal, truth.

In medieval times, pilgrims who reached Santiago often continued farther west to Cape Finisterre — the edge of the known world — to wash in the ocean and take a scallop shell home as proof that the path was complete.

Tendería holds both of these worlds at once — the earthly and the spiritual. Among the smell of fresh bread and the clink of glasses, you can still feel the breath of the old city and the distant echo of the pilgrim road stretching far to the west, toward the ocean and the stars.

Walking through the old streets of Bilbao, your eyes keep drifting upward to the balconies. One has geraniums and a small lemon tree. Another carries a yellow banner calling for support for refugees. And then there’s the white flag with the black silhouette of the Basque Country and the words “Euskal presoak eta iheslariak etxera” — “Basque prisoners and exiles, home.” It’s just cloth, but it carries the weight of decades: freedom, guilt, loss, memory — all tangled together.

These flags appear across the Basque north, from San Sebastián to Bilbao. For some they are a quiet plea for justice, a call to bring home those serving sentences for ties to the former militant group ETA. For others they are painful reminders — of fear, grief, and the years when violence touched nearly every family. In these flags the Basque story becomes visible again: a place where politics and everyday life have always overlapped.

Just below those balconies stands Larralde, a small café that has been open since 1910. Its door creaks, and the display case holds Carolina pastries and pastel de arroz. The smell of coffee, cream, and chocolate fills the doorway. If you didn’t know the history, you might think Bilbao is all sweetness and small pleasures.

But look up again and the façade tells another story. A flag hangs only a few meters above the cakes — a reminder that this city was shaped not only by sugar and flour, but also by struggle, ideas, and loss.

ETA — Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, “Basque Homeland and Freedom” — was born here, among young students determined to protect their language and identity under Franco’s regime. What began as a cultural movement turned into an underground force that carried out hundreds of attacks over decades. Some became national wounds: the 1974 bombing of a Madrid café that killed 13 people; the 1987 attack on Barcelona’s Hipercor supermarket, which killed 21, including children. And perhaps the most shocking — the 1973 assassination of Prime Minister Carrero Blanco, an explosion that launched his car into the air and marked the beginning of the end of the dictatorship.

Over time, Basque society grew weary of bloodshed. In 1997, after the kidnapping and murder of the young councillor Miguel Ángel Blanco, crowds across Spain filled the streets shouting “Basta Ya!” — “Enough!” From that moment, ETA’s support faded. In 2011 it announced a permanent end to violence; in 2018, its dissolution.

Today in Bilbao, history hangs right on the walls. Between houseplants and laundry, flags carry memories. Below them, old shop signs like Larralde keep everyday life moving forward, just as they did a century ago. And that is Bilbao in a single scene: pain and pride, bitterness and coffee, all living side by side — not canceling each other out, but reminding us that freedom begins with the right to remember.

The Cathedral of Saint James is the heart of old Bilbao — the place where the city’s spiritual and historical lines converge. Dedicated to the apostle James, patron of travelers and of the city itself, it stands as a northern echo of Santiago de Compostela, where his relics rest. Most of the cathedral was built between the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries in graceful Gothic style; the tower and main façade came much later, reshaped in nineteenth-century Neo-Gothic.

What makes this cathedral uniquely Bilbao is the way the old town, Casco Viejo, has grown right into its walls. Between the buttresses and around the apse you find lonjas — tiny shops and workshops that appeared over the centuries. This blending of sacred space with everyday life is typical of the old city: as Bilbao expanded, its commerce crept up to the church walls. Watchmakers, craftsmen, and small traders once worked in these narrow add-on spaces, turning the cathedral’s exterior into part of the city’s daily rhythm.

The main portal, with its thick carved wooden door, greets pilgrims walking the northern route of the Camino de Santiago. It marks a clear threshold: the noise of the streets behind you, the quiet of the sanctuary ahead. For centuries, merchants, travelers, and believers have entered through this doorway — people searching not only for the road west, but for a way toward their own sense of peace and clarity.

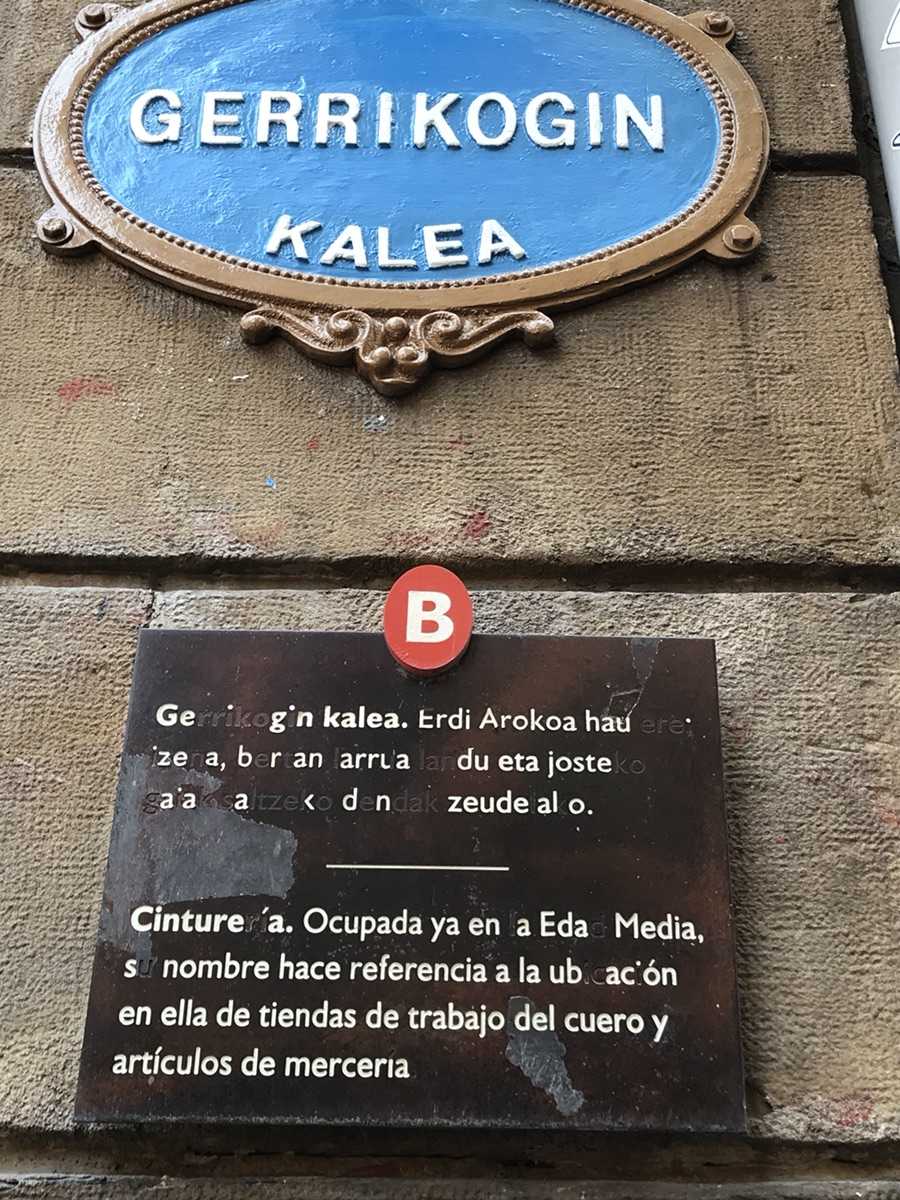

Gerrikogin Kalea — known in Spanish as Cinturería — is the old leather-workers’ street. Its name says exactly what once happened here: this was the place of belts, straps, and anything shaped by hand from tough, durable hides. The workshops lined the ground floors, their doors open to the street. You would have smelled leather and hot wax, heard the tap of hammers and the ring of metal buckles as craftsmen stitched belts, purses, and harnesses.

Over time, other trades settled in — tiny shops selling thread, buttons, ribbons, and everything needed for sewing. It became one of the classic mercerías of old Bilbao. The houses stand close together, typical of the original Seven Streets. Downstairs was always for work: bakers, tanners, merchants, all packed into a narrow strip of stone. Upstairs, behind the glassed-in balconies added in the nineteenth century, families lived their lives above the noise of their trade.

Today the tools have changed, but the rhythm remains. Coffee cups and wine glasses have replaced needles and knives; the smell of baking has overtaken the scent of tanned leather. Yet if you slow your step on the cobblestones, it almost feels as though the old workshops are still here, their echo woven into the street.

Standing in front of the Cathedral of Saint James, it feels as if the pace of time shifts for a moment. This is the center of Bilbao — not just geographically, but spiritually, the point from which the city’s story begins. A church stood here even before Bilbao became a city. In the founding charter of 1300, signed by Diego López de Haro, the temple is already mentioned, and from that moment it became the city’s spiritual axis. It was dedicated to Saint James, the patron of pilgrims, and it makes sense: the northern Camino route to Santiago de Compostela passed directly through Bilbao.

The cathedral is Gothic — long, narrow, disciplined — with three naves, the central one rising high above the others. Stone vaults rest on flying buttresses like ribs, and the whole building seems to breathe through its masonry. In the sixteenth century a sacristy and cloister were added, with an entrance directly from the street through the Angel’s Gate. That passage still feels like a threshold: one step takes you out of the city’s noise and into a pocket of quiet. According to old tradition, pilgrims entered the cloister through this doorway to rest after their long journey. Above the gate once stood an image of the Archangel Michael, protector and guide, so crossing under it was seen as walking beneath the wings of a guardian.

That is part of Bilbao’s charm: everything here has both form and meaning. Even the architecture speaks.

In front of the cathedral stands an eighteenth-century fountain — a stone vase above four lion heads from which water flows. It was created in 1785 by Luis Paret, an exiled painter who lived in Bilbao for several years. The fountain was originally part of the city’s new water system, yet for pilgrims it became a symbol of cleansing, renewal, and fresh strength for the road ahead.

Step a little to the side and you see flags hanging above the shops. The Ikurriña, the Basque flag: red for the land of the Basque Country, the green cross of Saint Andrew for liberty and self-rule, the white cross standing for faith and justice. Created in the nineteenth century, it has long since become more than a flag — it is a declaration of identity from a people who have always insisted on walking their own path.

Sometimes the Basque flag hangs beside the crest of Athletic Bilbao, and that combination says as much about this place as any history book. The crest carries the bear and oak of Gernika — symbols of Basque freedom — along with the old bridge and the church of San Antón, the sites from which the city grew. The club’s colors — red and white — are worn with fierce pride, and its unique rule is famous: only players born or raised in the Basque Country can wear the shirt.

The cathedral, the fountain, the flag, the football crest — together they read like one continuous story about Bilbao: a city where faith, work, honor, and play weave into a single language. Here, history isn’t something preserved behind glass. It lives in the stone, in the water’s murmur, and in the people who still carry their colors with pride.

If you turn off Calle Tendería and wander a little deeper into old Bilbao, you eventually come across a small fountain that is both charming and slightly comical — the Fuente del Perro, the “Dog Fountain.” The funny part is that there isn’t a single dog on it. Water pours from the mouths of three stone lions, and locals joke that the name stuck simply because “no dog has ever drunk from it.”

The fountain dates back to 1800, a moment when Bilbao was beginning to step out of its medieval tightness and into a more modern era. Its style is pure Neoclassicism — clean lines, balanced proportions, a clear nod to ancient architecture. The upper section looks like a tiny temple; the lower, like a sarcophagus, as if hinting at the quiet cycle of life and rest.

In its time, the fountain wasn’t just decoration. Before Bilbao had a central water system, people came here with pitchers, filling them for the day. In the evenings neighbors gathered around it — to share news, trade gossip, or simply cool off after a hot afternoon. It was a meeting point long before cafés and social networks existed.

Today the Fuente del Perro is one of those places where you can feel old Bilbao almost physically. It carries the city’s spirit — a mix of dry humor, pride, and unhurried life. If you stop beside the lion heads and listen to the water, it’s easy to imagine the same voices, the same laughter, the same slow rhythm that filled this spot two centuries ago. This is the heartbeat that still makes Casco Viejo so unmistakably alive.

Step past the “Dog Fountain,” and the street suddenly changes tone — this is where Bilbao starts grinning. It’s a strip of bars and pubs where the smell of fried anchovies, fresh coffee, and young wine hangs in the air, and conversations flow with the same ease as txakoli sliding into a glass. You don’t plan to stop here — your legs just decide for you.

Xukela is the heartbeat of this little row. Only a few steps from Fuente del Perro, the bar feels like a pocket of old Bilbao: wooden walls, sun-faded posters, framed photos that have been there forever, and a kind of warm noise that comes only from people who know a place by heart. There’s no shine, no performance — it’s all authenticity.

Locals walk in as if crossing their own threshold: they stand at the counter, order a glass of wine, and reach for a pintxo before it disappears. That’s the unwritten rule of Xukela — pintxos are for eating as long as they’re on the counter. Tourists look confused at first, then switch into the rhythm: here, nothing is served — life is simply happening around you.

This little “dog street” pulses with the same attitude that defines Bilbao itself: loud in the best way, a bit stubborn, and absolutely alive. Here, flavor and laughter are part of history — just as real as the stones beneath your feet.

In the old heart of Bilbao, there’s a spot where the city seems to tie sky, stone, and water together. On Pelota Street, number 10, stands an eighteenth-century palace known as Palacio Yohn — though locals simply call it La Bolsa. Built around 1727 on the site of a medieval tower, it’s a classic Baroque townhouse: heavy stone walls, tall windows, family crests carved above the doors. But if you lift your eyes a little higher, you’ll see something far more delicate — a small niche with the image of the Virgin of Begoña.

Begoña is the patroness of Bilbao and the whole region of Biscay. This little figure is a copy of the statue from the basilica on the hill, and from her niche she looks down on the old streets as if keeping watch over the people passing below. Beneath her is a marble plaque marking the height the water reached during the catastrophic flood of August 26, 1983. The old town was submerged, but the community survived — and the image of Begoña was placed here as a quiet thank-you for that survival. Walk past it today, and it still feels as if she’s holding the city in her hands.

There’s another small wonder tucked into these narrow lanes. Near the Cathedral of Santiago, set quietly into the pavement, is a tiny metal star — izarra in Basque. It marks the one point in all of Casco Viejo from which you can see the white silhouette of the Basilica of Begoña on the distant hill. Stand on the star, face north, and the buildings suddenly part just enough for the basilica to appear — a small revelation you discover with your own eyes.

And all of this lies within a few steps: a Baroque palace, a star hidden in the cobblestones, and a guardian figure watching over a city that learned to rise after the water. A little geometry of Bilbao — stone, faith, and a hint of quiet magic.

Walking through old Bilbao, where the narrow streets twist like the branches of an ancient tree, you eventually reach two places where the city’s past seems to breathe through the stones — Calle del Perro and Calle de la Torre.

Calle del Perro — “the dog street” — carries the city’s sense of humor. Long ago there was a fountain here with carved lion heads, though no one in Bilbao had ever seen a real lion. Dogs, on the other hand, were everywhere. So the “Lion Fountain” slowly became the “Dog Fountain,” and the nickname stuck for centuries. In medieval times this was a working street — traders watering their mules, saddle-makers repairing straps, leatherworkers cutting belts. Today the rhythm is the same, just updated: the clink of glasses, the smell of pintxos, laughter drifting from the bars. The whole street feels like the city smiling at itself — a reminder that history isn’t always solemn; sometimes it’s warm and familiar.

A few steps away, Calle de la Torre speaks in a different tone — deeper, heavier, like the echo of old families walking across stone. This was once the site of the Zurbarán family tower, one of the fortified houses that protected Bilbao in the fifteenth century. Many such towers stood here, each tied to a powerful lineage, each carrying a crest and a sense of pride. They disappeared during the nineteenth-century modernization, but their names remained — like bones of the old city beneath the new skin.

And there is something quietly striking about that. These Basque family towers feel spiritually close to the stone towers of Svaneti in the mountains of Georgia: the same thick walls, the same fierce sense of clan, the same idea of honor and self-reliance. Even the Basque language, euskara, with its unusual sounds and endings, seems to carry a faint echo of far-off Caucasian speech. Linguists once tried to prove a connection between the Basques and the peoples of the Caucasus — not a direct link, but something ancient, buried deep. Maybe they were wrong, or maybe they were just looking too closely to see the bigger picture.

Because when you stand on Calle de la Torre and look up at the houses where towers once stood, you feel something very similar to being in Svaneti: that stubborn sense of lineage, the feeling that the stone itself remembers who you are and where you come from. And maybe that’s the whole point — towers, languages, clans: these are traces of who we were long before we ever called ourselves nations.

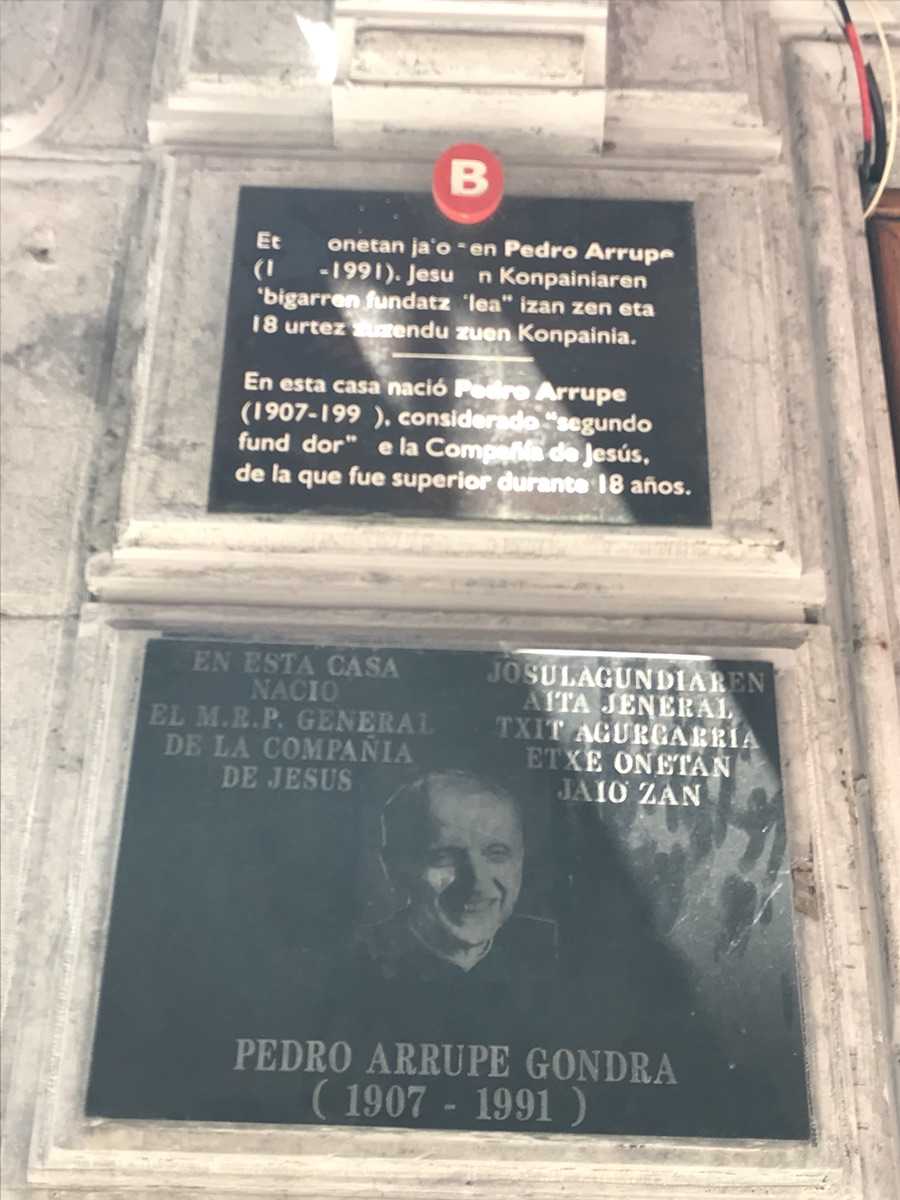

Pedro Arrupe Gondra was another Basque who reshaped the world — not by founding the Jesuit order like Ignatius of Loyola, but by renewing it centuries later and giving it a modern soul. He was born in 1907 in a modest house here in old Bilbao, marked today by a small plaque you could easily miss if you weren’t looking for it. It’s a surprisingly quiet birthplace for someone who would become the Superior General of the Jesuits, the global head of the order, and the person many call its “second founder.”

Arrupe lived like a bridge between eras. His leadership fell on the decades after the Second Vatican Council, when the Catholic Church decided to “open the windows” and breathe the air of a changing world. For the first time, Mass was celebrated in local languages instead of Latin; the Church affirmed human rights, acknowledged the value of science, and reached out to other faiths. Arrupe didn’t just support this shift — he embodied it.

He pushed the Jesuits beyond academic walls and into the lives of real people: the poor, refugees, and anyone living where faith intersects with suffering. Under his leadership, the order created the Jesuit Refugee Service, an organization that still works worldwide. Arrupe’s reforms weren’t about rewriting rules; they were about restoring the original heartbeat of the order — turning belief into action and compassion into a kind of spiritual clarity.

For Bilbao, he remains a symbol of how deeply rooted a modern person can be. He carried the strengths people associate with the Basques — simplicity, quiet determination, sharp intellect, and humanity. And every time you pass that unobtrusive plaque on the wall, it’s hard not to think how often the people who change the course of history come from the most ordinary doorways.

Calle de la Pelota is one of those names that carries more history than the street itself seems willing to reveal at first glance. The plaque here tells the story. The word pelota means “ball,” and in Basque the street is Pilota kalea — a direct nod to the traditional Basque sport pelota, the ancestor of both squash and tennis.

The street was laid out in the 15th century, when Bilbao began to grow beyond its original Seven Streets — Zazpi Kaleak. And right here stood the city’s first known fronton: an open playing court with a single wall where players batted a ball using their hands or early wooden rackets. The games became so popular that the entire street took on the fronton’s name. It wasn’t just a sports venue — it was a gathering place, a slice of Basque culture where competition, community, and everyday life blended naturally.

Today Calle de la Pelota feels like any other lively pedestrian street in Casco Viejo — bars, shops, people drifting by — but its name still holds the echo of those matches: the thud of the ball, the shouts of players, the crowd pressing in. It’s a reminder that in Bilbao, sport has always been a way of being together.

Just a short walk from Andra Mari Street — where the first Spanish ambassador to the Americas was born — stands a building that preserves a quieter, but no less important chapter of Bilbao’s past. On its façade you can still read the inscription:

Grupo Escolar Municipal de Múgica, año de 1917.

This was the old municipal school, built for the children of the old town — the boys and girls who ran through the narrow lanes between Calle Santa María and Calle de la Ribera, helped their parents in tiny shops, and dreamed of a life beyond the market stalls and the port.

The Múgica School was a symbol of a new century. The early 1900s brought Bilbao not only industry and ships, but also a belief in education as the city’s future. Here, every child was taught — regardless of background or income. Newspapers of the time called it “the school of equals,” and the name wasn’t poetic; it was policy. It reflected a city beginning to understand that progress wasn’t only steel and trade — it was opportunity.

The building still stands in Casco Viejo, surrounded by the same streets once filled with the ring of church bells and the shouts of market vendors. Its façade, crowned with the city’s coat of arms, is a reminder that the history of Bilbao isn’t made only of legends, diplomats, and merchants — but also of children who first discovered the world at a wooden desk under this very roof.

El Arenal was once a sandy stretch of land shaped by the curve of the estuary. In the Middle Ages, this area served as Bilbao’s shipyard zone — boats were built and launched from these banks. But starting in the 16th century the land slowly dried out, the shipyards disappeared, and the space turned into avenues and groves. El Arenal became a park — “the most delightful spot in town,” a place where people gathered at all hours.

For generations it was Bilbao’s favorite promenade. Gentlemen walked beside shopkeepers and office clerks; priests strolled carefully behind nannies; soldiers flirted with them under the shade of the trees. In 1817, the first theater of Bilbao was built here. It was replaced in 1834 by the Teatro de la Villa, designed by Juan Bautista de Escondrillas, which later suffered damage during the 1874 bombings. Between 1886 and 1890 the current theater was constructed — the one designed by Joaquín Rucoba, now known as the Arriaga Theatre, in honor of Bilbao’s most celebrated composer.

On the site of the former San Nicolás Inn — once the most important inn in the town — the headquarters of the Bank of Bilbao was built between 1862 and 1866. Designed by Eugène Lavallé, it became the financial symbol of the rising merchant class.

The famous Arenal lime tree was planted in 1816 and became a beloved landmark until a storm brought it down in 1948. And although El Arenal functioned as a public park, the waterfront beside it continued to operate as part of the port well into the 20th century.

The Arenal bandstand, altered over time but faithful to its purpose, still hosts concerts by the Bilbao Municipal Band and the traditional txistularis — Basque flute players accompanied by drums.

For many locals, the nearby Church of San Nicolás is simply the backdrop to their walks. Yet inside it holds remarkable Baroque altarpieces and sculptures by Juan Pascual de Mena — one of the finest examples of full Bizkaian Baroque.

A short walk away stands the Gómez de la Torre Mansion (1789–1791), one of the first neoclassical civil buildings in Bizkaia — austere, functional, and elegant in its simplicity.

In the 19th century, Calle Viuda de Epalza became the final expansion of the Old Quarter. It was lined with grand homes belonging to Bilbao’s wealthiest families, including that of Casilda Iturrizar, widow of banker Tomás José Epalza, whose name the street still carries.