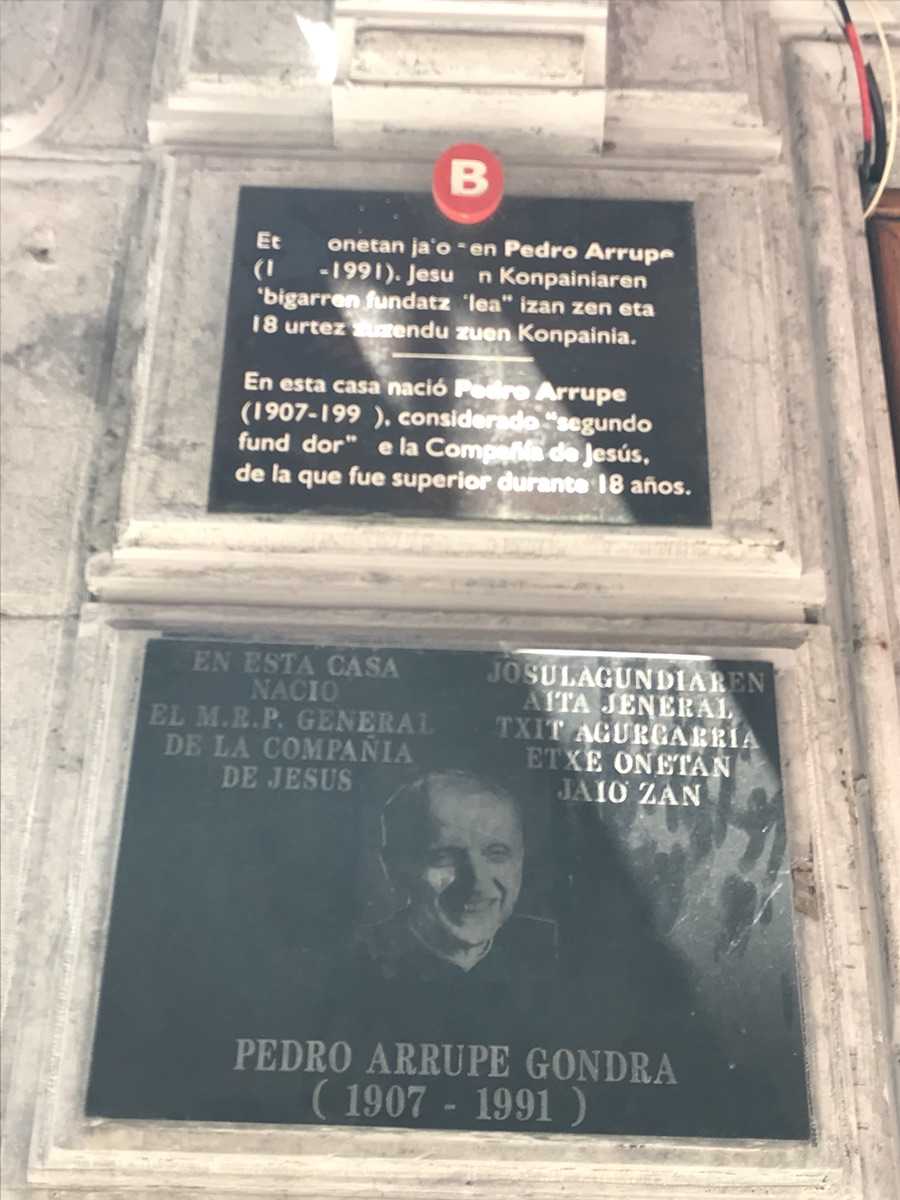

Pedro Arrupe Gondra was another Basque who reshaped the world — not by founding the Jesuit order like Ignatius of Loyola, but by renewing it centuries later and giving it a modern soul. He was born in 1907 in a modest house here in old Bilbao, marked today by a small plaque you could easily miss if you weren’t looking for it. It’s a surprisingly quiet birthplace for someone who would become the Superior General of the Jesuits, the global head of the order, and the person many call its “second founder.”

Arrupe lived like a bridge between eras. His leadership fell on the decades after the Second Vatican Council, when the Catholic Church decided to “open the windows” and breathe the air of a changing world. For the first time, Mass was celebrated in local languages instead of Latin; the Church affirmed human rights, acknowledged the value of science, and reached out to other faiths. Arrupe didn’t just support this shift — he embodied it.

He pushed the Jesuits beyond academic walls and into the lives of real people: the poor, refugees, and anyone living where faith intersects with suffering. Under his leadership, the order created the Jesuit Refugee Service, an organization that still works worldwide. Arrupe’s reforms weren’t about rewriting rules; they were about restoring the original heartbeat of the order — turning belief into action and compassion into a kind of spiritual clarity.

For Bilbao, he remains a symbol of how deeply rooted a modern person can be. He carried the strengths people associate with the Basques — simplicity, quiet determination, sharp intellect, and humanity. And every time you pass that unobtrusive plaque on the wall, it’s hard not to think how often the people who change the course of history come from the most ordinary doorways.

This walk is not just a stroll through the old streets of Bilbao — it’s a walk through the city’s memory. Everything here lies close together: the Gothic gates of Santiago Cathedral, the soft murmur of the “Dog Fountain,” the old plaques still marked by the great flood of 1983, and Bar Xukela, where the spirit of the city lives in a glass of wine and laughter at the counter.

We follow Calle del Perro and Calle de la Torre — streets whose names hold legends and the echoes of ancient family towers. At every turn, a story appears: about the Basques, whose defensive towers once stood like the stone houses of Svaneti; about Diego María Gardoki, the first Basque to serve as Spain’s ambassador to the United States; about Pedro Arrupe, the Basque priest who renewed the Jesuit order in the twentieth century.

Our path leads to the river where ships once lined the shore, and finally to El Arenal — the park where Bilbao learned to breathe, to love, and to listen to the quiet rhythm of its own heart.

This walk is like a simple, honest conversation with the city — no guide, no performance, just a friend who has a story waiting behind every corner.