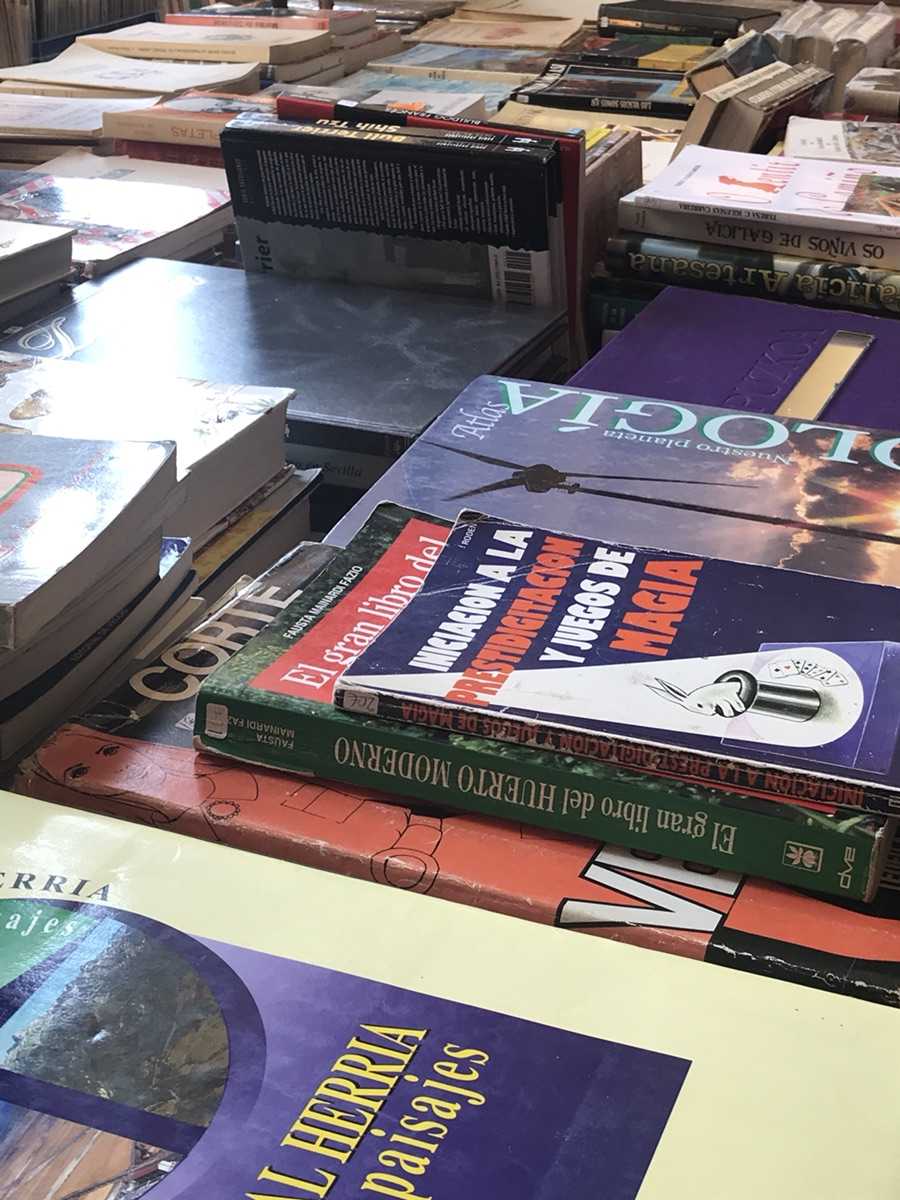

The Sunday antique market on Plaza Nueva reveals more than a love of old objects — it shows a particular Spanish way of treating memory, handwriting, and the written word. On the tables you find old pens, decks of cards, books — everyday things through which people once expressed themselves and left a trace of who they were.

Spanish writing culture has never been about formality; it’s about feeling. Here, people continued writing letters by hand long after the rest of Europe moved on. They cared about paper, ink, and even the rhythm of their handwriting. A good fountain pen wasn’t just a tool — it was an extension of thought.

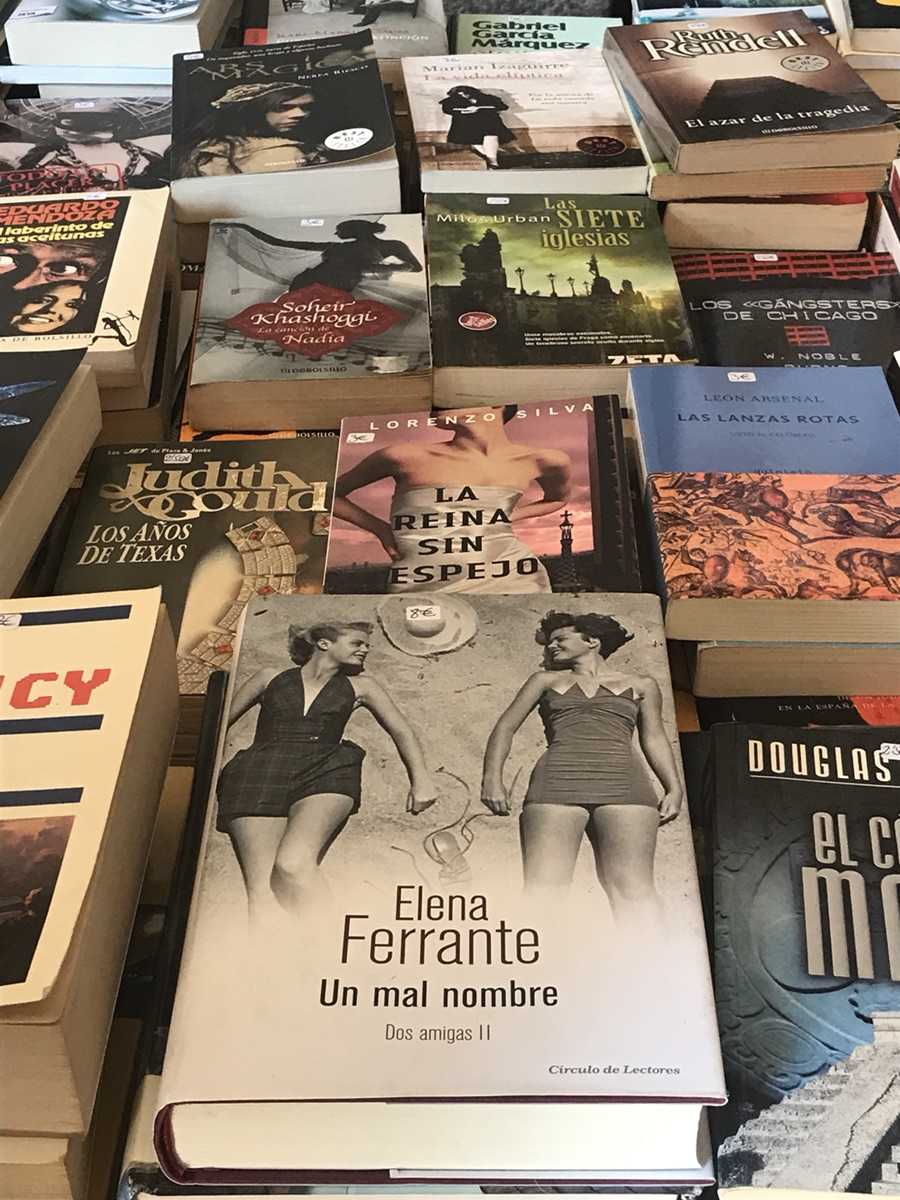

The books you find here are not random either. Many are novels and personal stories, focused on people and cities, where the inner world matters more than appearances. Spaniards read emotionally, almost as if they’re in conversation with the author — not as a task or a duty, but as a shared experience. That’s why each volume feels less like merchandise and more like someone’s memory placed gently on a table.

And this reveals a cultural difference. In England, writing, reading, and book collecting often reflect a tradition of order, intellect, and archival thinking — knowledge arranged into structure. In Spain, these same acts are tied to life itself. People write to express, read to feel, and save things so that emotion isn’t lost.

So the old pens and books at the market are more than antiques — they are signs of a deeply personal relationship with words. Spaniards turn writing into a continuation of human warmth, and perhaps that’s why their culture feels so alive even in objects that have long fallen out of everyday use.

This walk is not just a stroll through the old streets of Bilbao — it’s a walk through the city’s memory. Everything here lies close together: the Gothic gates of Santiago Cathedral, the soft murmur of the “Dog Fountain,” the old plaques still marked by the great flood of 1983, and Bar Xukela, where the spirit of the city lives in a glass of wine and laughter at the counter.

We follow Calle del Perro and Calle de la Torre — streets whose names hold legends and the echoes of ancient family towers. At every turn, a story appears: about the Basques, whose defensive towers once stood like the stone houses of Svaneti; about Diego María Gardoki, the first Basque to serve as Spain’s ambassador to the United States; about Pedro Arrupe, the Basque priest who renewed the Jesuit order in the twentieth century.

Our path leads to the river where ships once lined the shore, and finally to El Arenal — the park where Bilbao learned to breathe, to love, and to listen to the quiet rhythm of its own heart.

This walk is like a simple, honest conversation with the city — no guide, no performance, just a friend who has a story waiting behind every corner.