Walking through old Bilbao, where the narrow streets twist like the branches of an ancient tree, you eventually reach two places where the city’s past seems to breathe through the stones — Calle del Perro and Calle de la Torre.

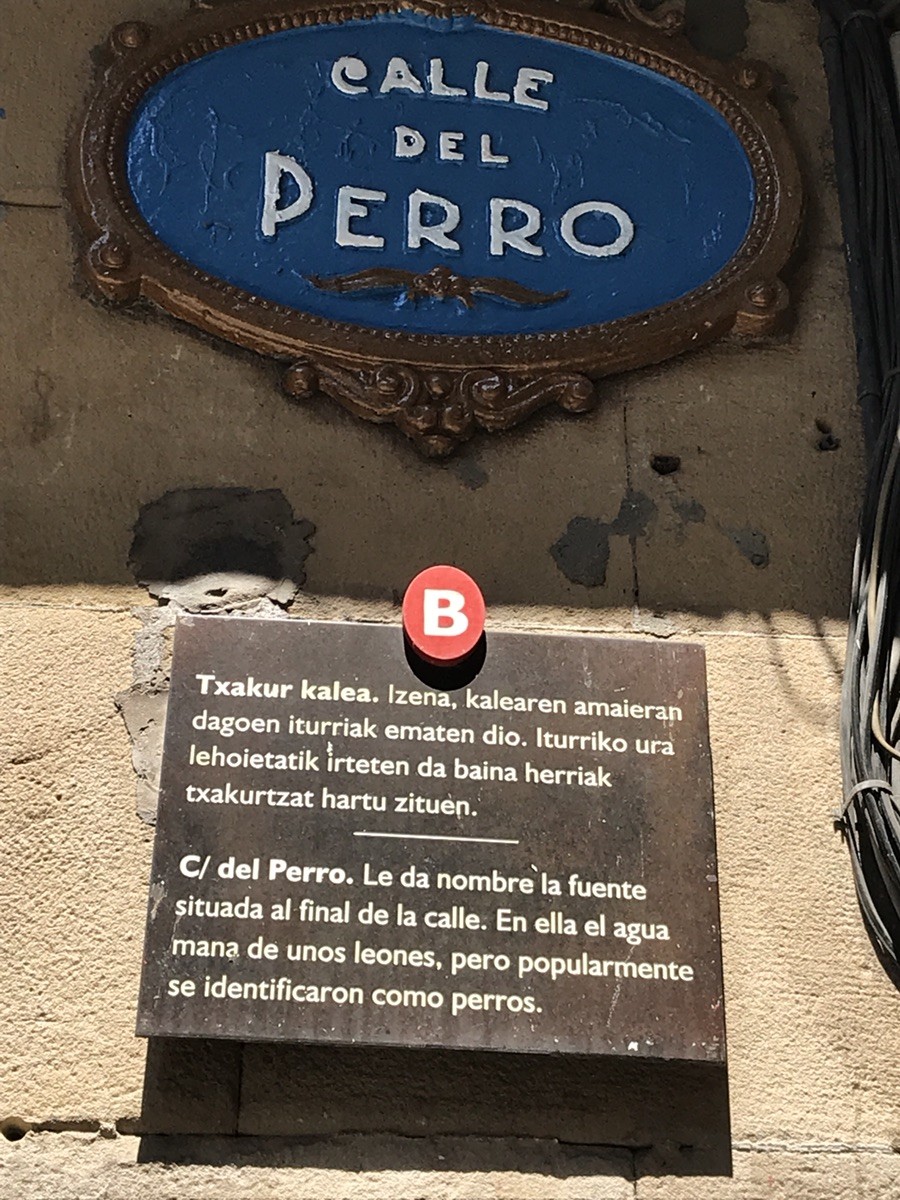

Calle del Perro — “the dog street” — carries the city’s sense of humor. Long ago there was a fountain here with carved lion heads, though no one in Bilbao had ever seen a real lion. Dogs, on the other hand, were everywhere. So the “Lion Fountain” slowly became the “Dog Fountain,” and the nickname stuck for centuries. In medieval times this was a working street — traders watering their mules, saddle-makers repairing straps, leatherworkers cutting belts. Today the rhythm is the same, just updated: the clink of glasses, the smell of pintxos, laughter drifting from the bars. The whole street feels like the city smiling at itself — a reminder that history isn’t always solemn; sometimes it’s warm and familiar.

A few steps away, Calle de la Torre speaks in a different tone — deeper, heavier, like the echo of old families walking across stone. This was once the site of the Zurbarán family tower, one of the fortified houses that protected Bilbao in the fifteenth century. Many such towers stood here, each tied to a powerful lineage, each carrying a crest and a sense of pride. They disappeared during the nineteenth-century modernization, but their names remained — like bones of the old city beneath the new skin.

And there is something quietly striking about that. These Basque family towers feel spiritually close to the stone towers of Svaneti in the mountains of Georgia: the same thick walls, the same fierce sense of clan, the same idea of honor and self-reliance. Even the Basque language, euskara, with its unusual sounds and endings, seems to carry a faint echo of far-off Caucasian speech. Linguists once tried to prove a connection between the Basques and the peoples of the Caucasus — not a direct link, but something ancient, buried deep. Maybe they were wrong, or maybe they were just looking too closely to see the bigger picture.

Because when you stand on Calle de la Torre and look up at the houses where towers once stood, you feel something very similar to being in Svaneti: that stubborn sense of lineage, the feeling that the stone itself remembers who you are and where you come from. And maybe that’s the whole point — towers, languages, clans: these are traces of who we were long before we ever called ourselves nations.

This walk is not just a stroll through the old streets of Bilbao — it’s a walk through the city’s memory. Everything here lies close together: the Gothic gates of Santiago Cathedral, the soft murmur of the “Dog Fountain,” the old plaques still marked by the great flood of 1983, and Bar Xukela, where the spirit of the city lives in a glass of wine and laughter at the counter.

We follow Calle del Perro and Calle de la Torre — streets whose names hold legends and the echoes of ancient family towers. At every turn, a story appears: about the Basques, whose defensive towers once stood like the stone houses of Svaneti; about Diego María Gardoki, the first Basque to serve as Spain’s ambassador to the United States; about Pedro Arrupe, the Basque priest who renewed the Jesuit order in the twentieth century.

Our path leads to the river where ships once lined the shore, and finally to El Arenal — the park where Bilbao learned to breathe, to love, and to listen to the quiet rhythm of its own heart.

This walk is like a simple, honest conversation with the city — no guide, no performance, just a friend who has a story waiting behind every corner.