Places to visit in Tel Aviv-Yafo

From Model Farm to Ohel Moed – tracing the historical layers of Tel Aviv’s Hashmal quarter

You’ll walk through the very heart of old Tel Aviv — a neighbourhood where orange groves, missionary dreams, and the glow of early electricity all intertwined. The journey begins at the Model Farm and its iconic water tower, the birthplace of irrigation in Eretz Israel. From there, we’ll trace the footsteps of the Ishma’ilov family — Mashhadi *anusim* who built rental houses and inns for Persian merchants, yet lost much of their fortune under dramatic circumstances. We’ll pause in Gan HaHashmal, the city’s second public garden, which has witnessed the romance of the 1920s, decline, and the wave of 21st-century gentrification. The walk culminates at the grand Ohel Moed Synagogue — the “Tent of Meeting” — where eastern communities claimed their rightful place in the growing city. This is a journey through layers of time: from water to electricity, from merchant houses to gardens and synagogues — a story where every street guards a secret and every building speaks for its generation.

Once, in the mid-19th century, the outskirts of Jaffa were home to a tidy *bayyara* — an orange grove with a well and a small workers’ house. The land belonged to a Christian merchant, Manuel Calis, until 1856, when an unlikely figure arrived: Albert Augustus Isaacs, a missionary from Jamaica. An Anglican priest, traveller, and photographer — born in the Caribbean, educated in England — Isaacs became convinced that under the scorching Palestinian sun he would build a model of modern agriculture: the **Model Farm**. It was meant to be a school of new farming — European ploughs, an irrigation tower, water channels, storehouses, and a manager’s residence. But Isaacs soon left, and another visionary took his place — Paul Isaac Hershon, a Jew from Buchach who had converted to Christianity and became a Talmud scholar. He tried to revive the farm, to teach local Jews and Arabs the “right” way to cultivate the land. Yet the soil proved heavier than ideals, and the dream faded.

Decades passed. The land was sold, and in 1923, the first power station in Eretz Israel rose on this very site — a white-stone building with tall chimneys and narrow windows, where Tel Aviv’s first electric lights flickered to life. The new neighbourhood took its name from the Hebrew word for electricity — **Hashmal**. And here entered a man of a different scale: **Pinhas Rutenberg**. Born in Romny, Ukraine, educated in St. Petersburg, a revolutionary once linked to the murder of Father Gapon, later an engineer in Italy, his life pulsed like high voltage. In Italy, he befriended Jabotinsky and Weizmann, and when he came to Palestine, he already had a plan: to build a nation powered by water. He founded the **Palestine Electric Corporation**, bringing light to Tel Aviv and Haifa and building the hydroelectric station at Naharayim. People called him *Zaken HaHashmal* — “the old man of electricity.”

Stories surrounded his private life — whispers of a librarian, a son who became an engineer in the Soviet Union, even a descendant who joined the *Chelyuskin* Arctic expedition. Rutenberg never confirmed a thing, preferring to be remembered not as a man of secrets but as the one who gave the country light.

Today, the area looks completely different. The **Bat Sheva Tower** rises over the remnants of the Model Farm, surrounded by offices and cafés. Yet the white power-station building still stands, and the restored farmhouse hides between skyscrapers. The city has changed, but memory remains: here began the story of Tel Aviv’s first orange grove and missionary dream, here its first lights were lit, and here Rutenberg built his empire of electricity. Walk down HaHashmal Street today, and you can still feel history breathing beneath the asphalt.

Before you stands one of the oldest surviving buildings of the former Model Farm, its stone walls and arched windows hint at its past as an agricultural warehouse, a place once filled with the rhythm of rural life. But if you listen closely, the story carries you into the 20th century. In the 1940s, the **Old Central Bus Station** of Tel Aviv rose nearby, quickly becoming the country’s central transport hub — the point where all roads met. Around it grew a buzzing microcosm of markets, cheap hotels, and repair shops. Yet along with the noise and motion came the city’s darker shades — overcrowding, poverty, and petty crime. Locals even called the Hashmal–Aviv zone “the belly of Tel Aviv,” a place where buses ruled by day and the streets ruled by night.

With time, the station aged and was moved south, but the spirit of those decades still lingers. It was this mix — the 19th-century farm, Rutenberg’s industrial power, the roar of the old bus station, and the hardships of urban life — that gave the neighbourhood its character. Today, the area is reinventing itself: historic façades are being restored, cafés and co-working spaces fill old courtyards, and new apartments rise beside century-old stone. Standing before this building, it’s easy to imagine the scents that once marked its eras — orange blossoms, diesel smoke, fried street fish — now replaced by the hum of students and designers shaping yet another layer of Tel Aviv’s story.

We leave Menachem Begin Boulevard — once the road from Jaffa to Petah Tikva — and turn onto Barzilai Street. In the early 20th century, this was the main entrance to the Hashmal quarter from the “Petah Tikva road.” The street was named after Dr Barzilai, one of the first physicians and public figures of the Yishuv. Look around: here, the layers of old and new blend in the most unexpected way. Beside the wall stands a frozen relic — a **Fiat 127**, the compact Italian car produced from 1971 and introduced to Israel in the mid-’70s. It was the dream car of the middle class — teachers, engineers, small business owners — affordable, efficient, and with a touch of European flair. For many Israelis, it was their first family car and a quiet badge of success.

It also evokes the country’s own brief automotive chapter. In the 1950s and ’60s, Israel tried to build its own cars: in Haifa, the **Kaiser-Frazer Israel** factory first assembled American models. It later produced the legendary **Susita**, a small fibreglass car that became a national icon. Government offices bought fleets of them, and for a while, the Susita ruled Israeli roads. But soon, imported cars like Fiat, Renault, and Simca replaced it, symbolising the shift from local ambition to global modernity.

So, standing here on Barzilai Street beside this pale-blue Fiat, you’re not just looking at an old car. You’re seeing a fragment of history — where the road to Petah Tikva once began, where the Hashmal quarter took shape, and where the dreams of orchards, electricity, and an Israeli automobile industry all met on the same strip of asphalt.

The tower peeking out between the buildings is the ancestor of innovation in the Land of Israel — the very first of its kind. In the mid-19th century, missionary Albert Isaacs built a well, a pump, and the first water tower in Jaffa on his **Model Farm**. Water was lifted to the top and flowed down through irrigation channels to the orchards — a technological leap from buckets and cisterns to a system of steady pressure. That simple idea made large-scale citrus cultivation possible and became a model for future settlements.

A few decades later, the Baron’s colonies adopted the same concept. In **Zikhron Yaakov**, a “very advanced” tower appeared in 1891. In **Rishon LeZion** in 1898, the Rothschild administration built its own, designed by architect A. Varon, complete with reservoirs and arched distributors that watered both orchards and the public garden. Wells had been drilled there since 1883, but it was the tower that made water a managed, communal resource.

Soon, urban Tel Aviv took up the torch: new towers rose across the young city, like the one on Mazeh Street (1924, engineer Arpad Gott). And beside the old Model Farm, the first power station flickered to life. From water to electricity, the principle remained the same — to store energy and distribute it to all. What began as a farmer’s experiment became the blueprint of urban infrastructure, shaping the neighbourhoods that grew around it.

From time to time, Jewish history has been scarred by sudden waves of violence. One such tragedy struck in 1839, in the Iranian city of **Mashhad**, when a mob incited by religious fanatics stormed the Jewish quarter — killing dozens, destroying synagogues, and forcing the entire community of about forty families to convert to Islam. From that moment, they became known as the *Mashhadi anusim* — “new Muslims” who outwardly followed Islam but secretly lit Sabbath candles and baked matzah behind closed doors. Their story echoed that of the Spanish *marranos*: hidden faith, quiet resistance, and survival through commerce.

They turned to what they knew best — trade in silk, carpets, and jewels — and their caravans carried them far beyond Iran. Many settled in **Bukhara** and **Samarkand**, where Jewish life flourished openly, and there they learned the art of business on a grand scale, sometimes marrying into Bukharan families. From Central Asia, their path led west — across the Caucasus and Turkey — toward the Mediterranean, to **Jaffa** and the emerging **Tel Aviv**.

Iran itself was turbulent. Just a decade earlier, in 1829, the Russian diplomat **Alexander Griboedov** had been murdered in Tehran — a warning of how easily religious fury could ignite against outsiders. The Mashhad pogrom of 1839 was another spark from that same fire, one that burned the most vulnerable. But in Ottoman Palestine at the turn of the 20th century, the Mashhadi Jews found something they hadn’t known for generations — the freedom to live openly as Jews.

Families like the **Ishma’ilovs** began to build homes, inns, and income properties. In 1925, on **Barzilai Street** in the **Hashmal quarter**, they erected the **Beit Ishma’ilov**, designed by architect **Dov Tschudnovsky** in an elegant eclectic style. The building held nine apartments, with stained-glass doors and wrought-iron balconies — symbols of refinement and success. Restored in 2012, it still bears the name of its original owner, **Ephraim ben Yoel Ishma’ilov**.

By then, the Mashhadi community had settled comfortably in the best neighbourhoods of Tel Aviv and Jaffa. No longer hiding their faith, they became known as prudent investors and proud urban citizens, their houses lining Barzilai, Montefiore, and Allenby streets. Standing before Beit Ishma’ilov today, one can trace a remarkable journey — from the persecution of Mashhad, through the markets of Bukhara and the caravans of Persia, to the open sunlight of Tel Aviv, where a once-hidden community finally found both belonging and permanence in stone.

In the very heart of old Tel Aviv, on HaHashmal Street, stands a tower — a silent monument to the time when the city was still learning how to be a city. Its story begins earlier than it seems: before the current reinforced-concrete structure was built in 1925, a stone tower stood here — the original water tower of the **Model Farm**. It was part of a late Ottoman-era vision to create an exemplary agricultural enterprise that would serve as a school and model for Jewish farmers, combining labour with science.

When engineers of a new era arrived in the 1920s, the old stone structure gave way to a new one — modern, rational, and precise. It was built by two men: **Arpad Gut**, a Hungarian engineer who brought reinforced concrete knowledge, and his partner **Berman**, a man almost erased from history. Together, under the firm **Gut & Berman Engineers**, they inscribed their legacy into the fabric of Tel Aviv — in its water towers, industrial buildings, and structural networks.

The HaHashmal tower was more than just a reservoir. At its base once operated a small store called **Sha’ar HaZol**, where locals bought bread, sugar, kerosene, and newspapers. Later, it housed the city’s water department workshop, and during wartime, it served as an observation post. In the 1990s, as Tel Aviv began to turn its gaze back to its past, the tower was restored, and a faint trace of the old lettering remained on its façade — a reminder that everything began with water, light, and the people whose names have nearly vanished with time.

Of **Berman**, no archives remain — no birthplace, no photographs, no date of death. Only a surname in an old technical document, and his invisible mark — in the proportions, the seams of concrete, in the way morning light falls along the tower’s curve. His name is gone, but his work endures — and perhaps that is the most valid form of a city’s memory: to remember those who built it, even when no one recalls where they came from.

House No. 15 on HaHashmal Street stands directly opposite the old water tower — the same one that once belonged to the Model Farm and became a prototype for the future of Jewish agriculture. The tower, built at the end of the 19th century, later inspired the famous water tower in Rishon LeZion — the birthplace of this house’s architect, **Ben-Zion Ginsburg**. Fate seemed to draw a perfect symmetry: the architect built his home facing the tower, continuing its story — but now in the language of urban architecture.

Ginsburg was a man of his age — elegant, secular, and flamboyant. He dressed with European precision, his suits perfectly tailored, and he had a fascination with cars, still a rarity in the 1920s. Trained at the **Zurich Polytechnic**, he absorbed the spirit of European modernism and refined rationalism. He lived and worked across Europe and spent several years in **Cyprus**, designing hotels and public buildings. There, his style matured — a blend of engineering precision and understated ornamentation.

The house, built in **1925** for his wife **Sarah**, became a bridge between Europe and the emerging Tel Aviv. Its symmetrical façade, tall arched windows, rhythmic columns, and well-balanced proportions embodied the eclectic spirit of the time — disciplined yet romantic. It seemed to declare: “Here begins a new life, on a land where even the stone remembers the farm, the water, and the labour.”

By the 1950s, after years abroad, Ginsburg returned to Israel — to the city that now bore his early works. The tower across the street had already become a monument, and his own home, a quiet part of HaHashmal Street’s living history.

The Dubitsky House at 19 Mikveh Israel Street is more than just a building — it’s a small human drama inscribed in the symmetry of its façade and in the fate of a city learning to stand on its own. It was built in 1925 by **Yitzhak and Hana Dubitsky**, a couple who seemed to have everything aligned: a bit of capital, some ambition, and a deep desire to belong to the new world. They commissioned **Yehuda Zuckerman**, an architect of the German school who blended European rigour with Mediterranean warmth. His style was distinctive — clean lines, balanced symmetry, a central stairwell volume, and a touch of Art Deco grace.

Zuckerman wasn’t an avant-gardist, but neither was he nostalgic. His buildings bridged tradition and what would later become known as the *White City*. The Dubitsky House turned out almost perfect: a harmonious façade, elegant balconies, precise proportions. Inside — high ceilings, cool rooms, and a staircase leading to the roof, where at night one could see the lights of Jaffa. Hana hosted tea gatherings, neighbours dropped by with their children, and Yitzhak dreamed of a future where, behind every street number, stood the word “city.”

Then came **1931**. The economic crisis hit hard — debts, repossessions, furniture sold through public auction. *Haaretz* reported dryly: “Sold — an armchair, a sofa, a clock, a desk.” A house built on hope had become a reminder of how quickly stability can collapse. By **1936**, the family had moved to **Hissin Street**, and new owners — **Daniel Sporta** and **Yaakov Birisi** — added a floor, commissioning **architect Hanoch Caspi**. Sporta was practical; Birisi, a Sicilian entrepreneur, saw not memory but investment. They kept Zuckerman’s façade but changed its soul — the house stopped being a story and became real estate.

It’s said that the Dubitsky sons, **Michael and Gabriel**, never returned. One moved to Haifa, the other abroad. Their fates dissolved into time, like the house itself, nearly swallowed by new construction — until **architect Nitsa Smok** restored it in **2018**. The façade was cleaned, the balconies straightened, the stairwell reopened to light — and the old house began to breathe again.

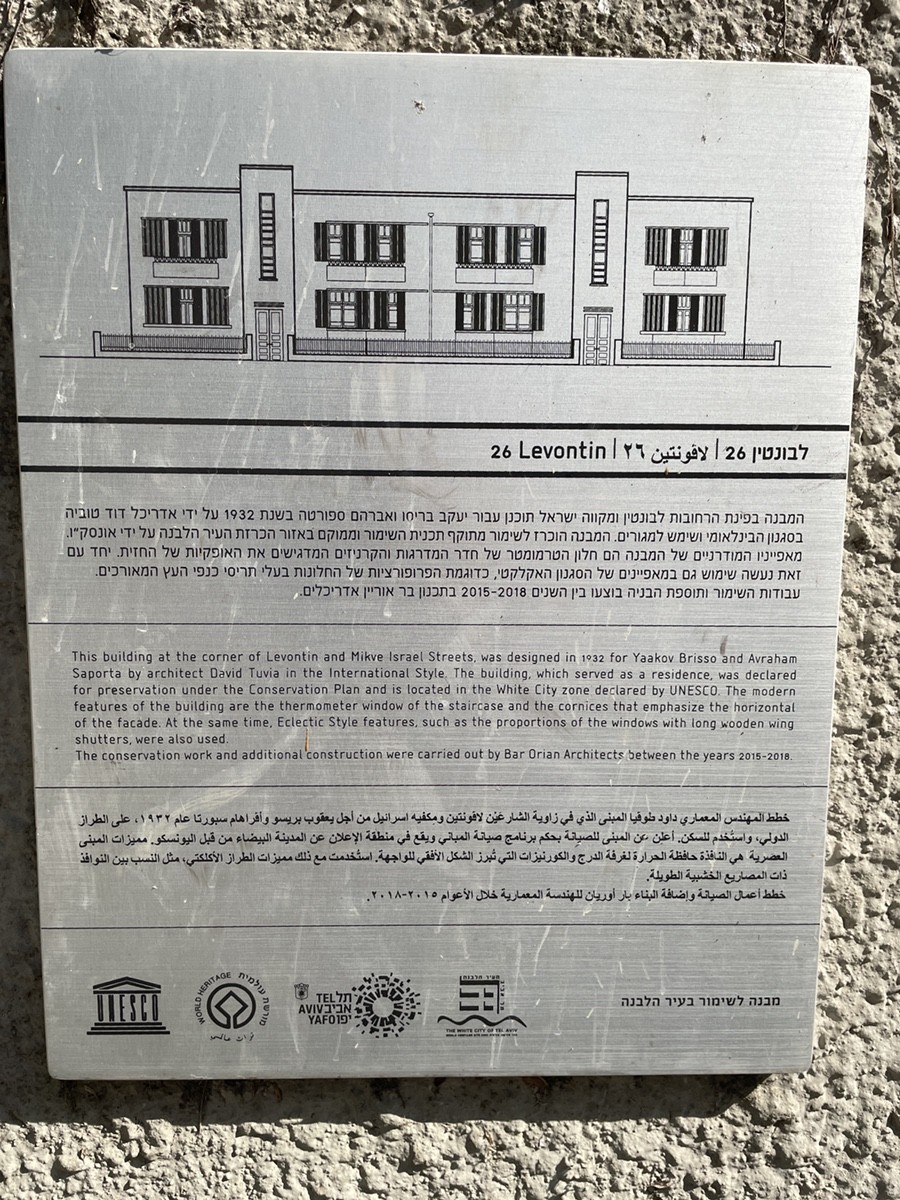

The house at the corner of Levontin and Mikveh Israel Streets was built in 1932, at a moment when young Tel Aviv, weary of suns and flimsy shacks, began to see itself as a true European city. The clients, **Yaakov Brisso** and **Avraham Saporta**, came from Levantine merchant families whose trade revolved around port shipments, coffee, textiles, and small real estate ventures. The building was more than an investment — it was a declaration of belonging: *we are no longer settlers; we are citizens.*

Architect **David Tuvia** chose the language of the new era — the **International Style**, where restraint itself became a form of elegance. He introduced a “thermometer window” — a vertical strip of light cutting through the staircase — and gave the house a sense of balance and airiness, like the sea breeze that carried with it faith in order and progress.

The **Saporta** family lived there until the early 1940s, after which the property passed to **Lea Wildenberg**, the widow of an engineer from the Electric Company, and later to **Eliezer Toktli**, a stationery merchant whose grandchildren still reside in the neighbourhood. After decades of neglect, the house was rescued by **Bar Orian Architects**, who restored its original proportions, discreetly added an upper floor, and preserved the façade — where the city’s story still breathes softly through the shade of its shutters.

House No. 17 on HaHashmal Street stands almost directly across from the old power station — and that’s no coincidence. Its owner, **Moshe Waldman**, was the chief engineer of the Electric Company in Tel Aviv — a man who quite literally lived among transformers, grids, and circuits. The house was designed in **1933** by architect **Aryeh Strimer**, at the height of the Functionalist era. Its clean cubic form, cantilevered balconies, and “thermometer window” running along the staircase all reflect a devotion to light, air, and precision — as if drawn straight from an engineer’s blueprint.

Waldman built the house not only for his family but also with space for his work: several rooms served as storage for technical equipment. Colleagues used to joke that if something broke at the power station, you could knock on his door — he’d come out in his work robe and fix it himself. The house became a quiet symbol of Tel Aviv’s first generation of engineers — people for whom electricity was not a metaphor but a calling.

Today, the building is part of the **White City** and protected as a **UNESCO World Heritage Site**. In **2017**, architects **Ma’oz and Price** restored it, reinstating its original proportions and the precise, confident geometry with which it was conceived. This house stands not just as a memory of an era, but as a monument to its precision — and to the human faith in mastering the power of light.

The house at 16 Levontin Street was built in 1925, when Tel Aviv was beginning to find its own architectural voice. Designed by **Avraham Abushdid**, it embodied the **eclectic style** of the period — symmetrical façades, arched windows, decorative stucco, balustrades, and a small central tower with an oval window. The house stood at a crossroads where the sandy road from Mikveh Israel led toward the city centre, serving not only as a residence but also as a marker of social standing.

Here lived **Leah**, the architect’s sister, with her husband **Itamar Ben-Yehuda**, grandson of **Eliezer Ben-Yehuda**, the founder of modern Hebrew. Their presence gave the house a special cultural resonance: its rooms echoed with Hebrew conversation, debates over words, and dreams of a new language for a new nation.

In the 1990s, like many buildings in the area, it was converted into offices. But between **2017 and 2020**, architects **Bar Orian** and **Kahana** restored the building, returning its original structure and harmony while adding a discreet modern upper floor. Today, the house once again looks as if it could tell not only its own family story, but also that of a city born from words, lines, and light.

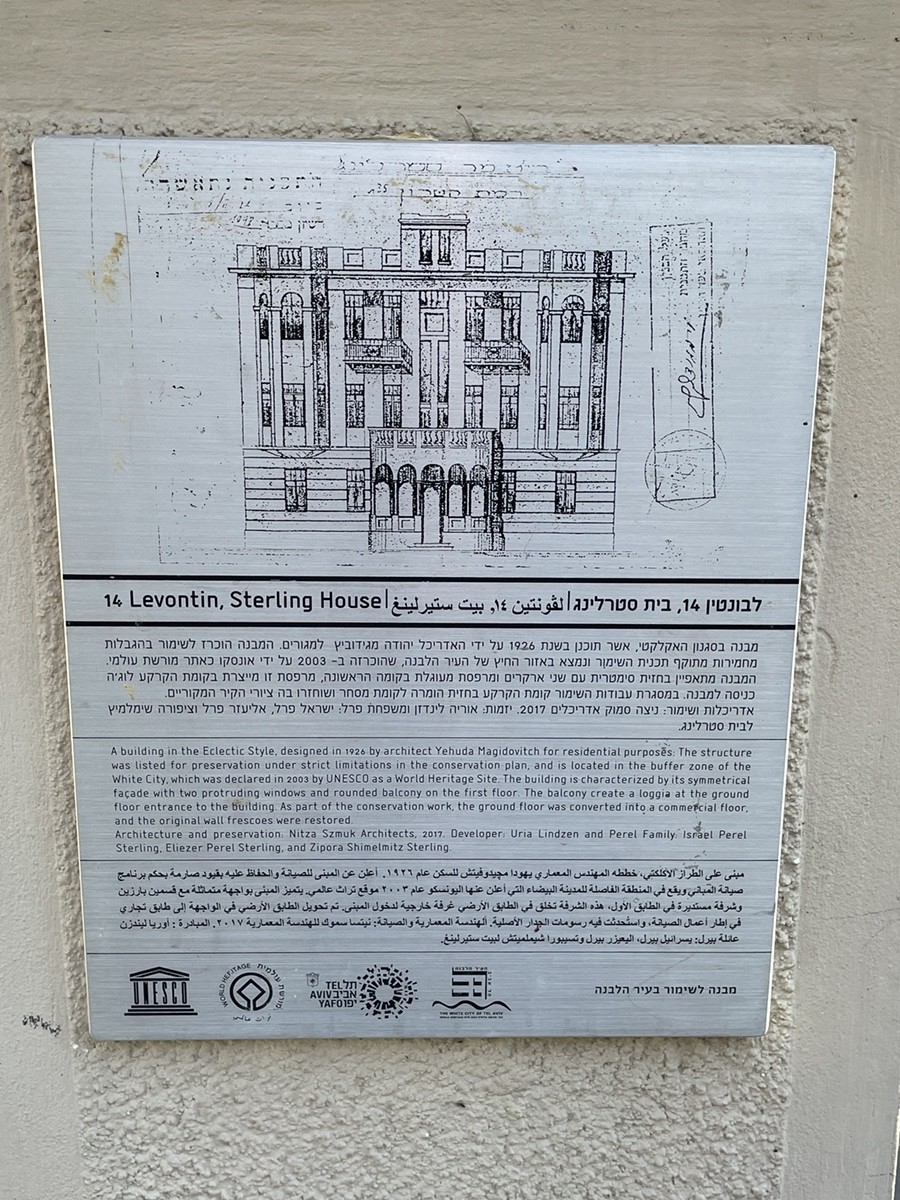

The Sterling House at 14 Levontin Street was born in 1926 at the hand of **Yehuda Magidovitch**, the master architect of early Tel Aviv, who knew how to weave East and West together. The **Sterling family commissioned the house** — some records name Zvi Sterling, others Eliezer and Tzipora Sterling — an affluent Ashkenazi family active in trade and real estate. Their home became both an investment and a statement of success, marking their place in the expanding heart of the young city.

The façade is a pure example of Tel Aviv’s **eclectic style**: projecting bay windows, a symmetrical rhythm of openings, and above the entrance, an arched balcony-loggia, from the 1930s, shops operated beneath its ground-floor arches, with signs in Hebrew, Russian, and English — a glimpse of the city’s multilingual pulse. The building stood within the area later designated by **UNESCO (2003)** as the buffer zone of the *White City*, and from the start it embodied dignity, prosperity, and modern urban identity.

Over the decades, the house’s ownership mirrored the city’s own transformations. In **1935**, Sterling sold it to **Yitzhak Shaltiel**, a merchant dealing in oils and provisions. By **1948**, the owner was **Lea Wildenberg**, whose refusal to build a bomb shelter prompted a tenants’ protest, as recorded in municipal correspondence. Shortly thereafter, in **1948–49**, the property passed to **Eliezer Toktli**. The inventory of the time lists three floors, twenty-four rooms, and a patchwork of rooftop additions — one of them an unauthorised carpentry shop. Like much of the neighbourhood, the building declined with time. In **1977**, resident **Reuven Cohen** wrote to the city: “The staircase is unsafe — a disaster may occur.” The house was added to the registry of “dangerous structures,” a status reaffirmed in **2011**.

Yet history loves its reversals. In **2017**, architect **Nitsa Shmuk** began a careful restoration, uncovering stairwell wall paintings beneath layers of plaster, reviving the prewar façade’s sculptural depth, and reorganising the interior: seven apartments above, two shops below, a discreet elevator, and new systems seamlessly integrated into the old frame.

Today, **14 Levontin** once again reads as it was meant to: the loggia greets the street, the bay windows hold the rhythm, and commerce hums again beneath the arches. Behind this quiet symmetry, one can still hear it all — the ambition of the Sterlings, the pragmatism of Shaltiel, Wildenberg’s dispute, postwar decline, Cohen’s plea, and, finally, the cautious joy of renewal. The house has not merely survived; it has become a chronicle of the neighbourhood itself — a layered testament to a century of life in Tel Aviv.

Hard times create strong people; strong people create good times; good times create weak people; and weak people bring back hard times. So goes the cycle of a city’s life. The **Ishma’ilov family**, descendants of the Mashhadi *anusim*, belonged to the generation of the strong — those who built Tel Aviv in the 1920s and 1930s. They erected income houses across the city and supported their fellow Mashhadi merchants wherever they could. Even their hotel on Montefiore Street was conceived as a haven for traders in carpets and jewellery from Persia and Bukhara.

But every story has a turning point. In **1935**, **Ephraim Ishma’ilov** died at the age of 53, and soon after, his heirs lost control of the *Hotel Ishma’ilov*. According to family lore, the building was gambled away to Georgian real estate merchants named **Makhashvili**. Both municipal records and business archives now preserve traces of this tale. Later generations of the family emigrated to the **United States**, settling in **Great Neck, New York**, where a large Mashhadi community eventually formed. In Tel Aviv, their name still appeared in the address books of the 1950s — no longer as developers, but simply as residents.

The same rhythm of rise and decline shaped the fate of the garden before us. Originally called **Gan HaSharon**, it was the first official public green space of the **Ramat HaSharon quarter**, founded in 1921–1922. The initiative came from residents, and Tel Aviv’s municipality granted the land under **Meir Dizengoff**. Unlike the empty lots between Allenby and Ahad Ha’am — once private, informal playgrounds for neighbourhood children — Gan HaSharon was planned as a true European-style park.

Over the decades, the garden mirrored the neighbourhood’s fortunes: from the romantic “**Garden of Kisses**” of the 1920s to a zone of decline, drugs, and prostitution by the late 20th century. Only after **2000** did it begin to bloom again — gentrification, restoration, cafés, and design studios reshaped its life. And now, standing here, one can sense the city’s eternal rhythm repeating itself: hard times, strong people, good times — and once more, the trials that precede renewal.

In the 1920s, Tel Aviv was still searching for its identity. To the north stretched Rothschild Boulevard with its elegant European villas and the grand Ashkenazi synagogue; to the south roared **Rutenberg’s power station** in the Hashmal quarter, designed by **Yosef Berlin**. Between them lay an empty stretch of land — a void that unexpectedly became the stage for the Sephardic community’s voice.

Two Jews from Aden, **Shalom Aharon Levy** and **Shlomo Yitzhak Cohen**, had purchased the plot as an investment. But the city’s Sephardic Chief Rabbi, **Ben-Zion Meir Hai Uziel**, saw a greater purpose: to create a spiritual and communal centre for the Jews of the East — one that would stand on equal footing with the Ashkenazi institutions. At his urging, the land was donated, and in **1923** the cornerstone was laid for a new synagogue.

Architect **Yosef Berlin**, the same who designed the nearby power station, envisioned a monumental building in the **Art Deco** style, crowned with a high dome. Thus rose the **Ohel Moed Synagogue** — the “Tent of Meeting.” Its biblical name referred to the Tabernacle in the desert, where all the tribes of Israel gathered—and in this new city, it served the same role. It became a house of prayer and assembly for diverse eastern communities: Adeni, Bukharan, and Balkan Jews. The **Sephardic rabbinate** of Tel Aviv also found its home here.

The logic of history is clear: the Ashkenazim had built the centre, while the Sephardim sought their own voice → the land fell into the hands of generous Adeni donors → Rabbi Uziel insisted on its sacred use → Berlin gave the vision architectural form. And just as Moses’ tent once stood at the heart of the encampment, so **Ohel Moed** rose in the middle of Tel Aviv — declaring that the city was not only a “little Europe,” but a home for all the traditions of the Jewish people.