The Sterling House at 14 Levontin Street was born in 1926 at the hand of **Yehuda Magidovitch**, the master architect of early Tel Aviv, who knew how to weave East and West together. The **Sterling family commissioned the house** — some records name Zvi Sterling, others Eliezer and Tzipora Sterling — an affluent Ashkenazi family active in trade and real estate. Their home became both an investment and a statement of success, marking their place in the expanding heart of the young city.

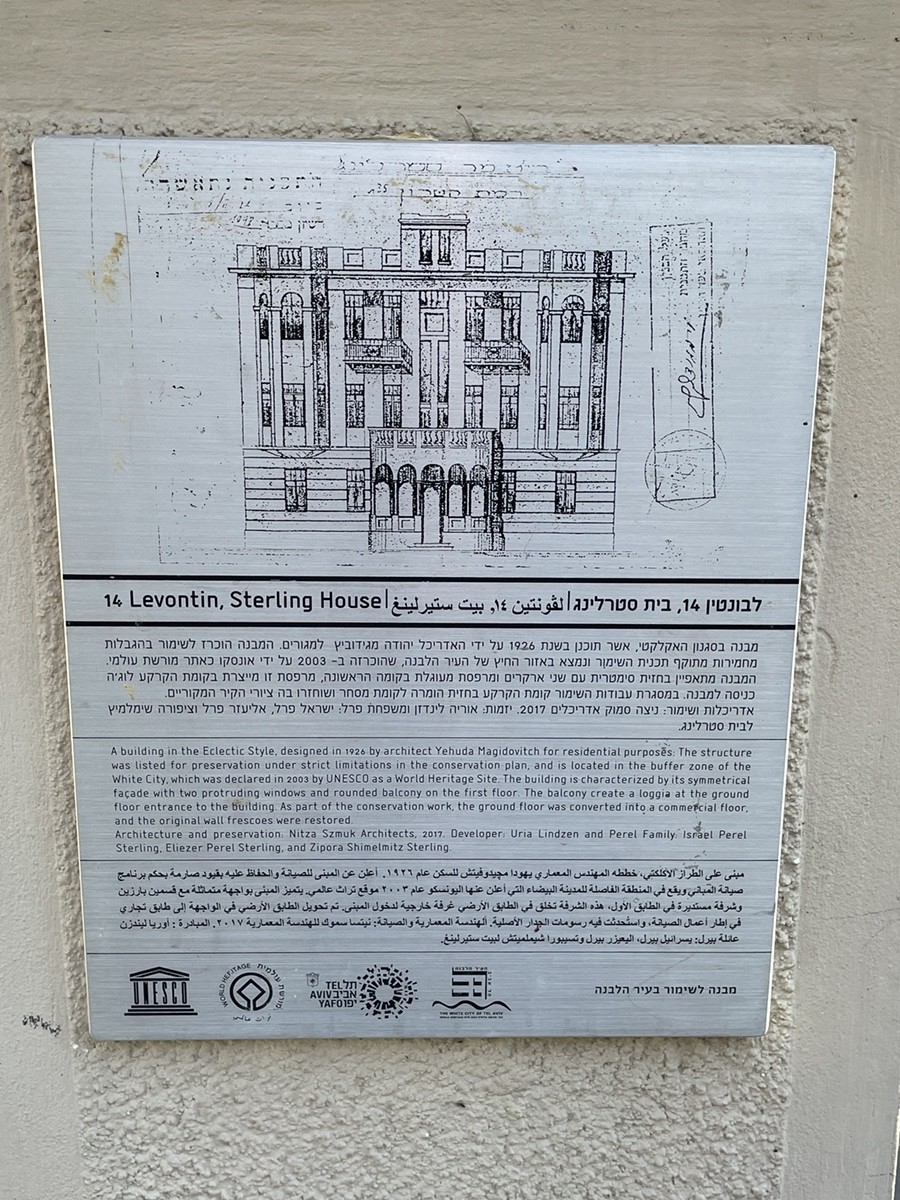

The façade is a pure example of Tel Aviv’s **eclectic style**: projecting bay windows, a symmetrical rhythm of openings, and above the entrance, an arched balcony-loggia, from the 1930s, shops operated beneath its ground-floor arches, with signs in Hebrew, Russian, and English — a glimpse of the city’s multilingual pulse. The building stood within the area later designated by **UNESCO (2003)** as the buffer zone of the *White City*, and from the start it embodied dignity, prosperity, and modern urban identity.

Over the decades, the house’s ownership mirrored the city’s own transformations. In **1935**, Sterling sold it to **Yitzhak Shaltiel**, a merchant dealing in oils and provisions. By **1948**, the owner was **Lea Wildenberg**, whose refusal to build a bomb shelter prompted a tenants’ protest, as recorded in municipal correspondence. Shortly thereafter, in **1948–49**, the property passed to **Eliezer Toktli**. The inventory of the time lists three floors, twenty-four rooms, and a patchwork of rooftop additions — one of them an unauthorised carpentry shop. Like much of the neighbourhood, the building declined with time. In **1977**, resident **Reuven Cohen** wrote to the city: “The staircase is unsafe — a disaster may occur.” The house was added to the registry of “dangerous structures,” a status reaffirmed in **2011**.

Yet history loves its reversals. In **2017**, architect **Nitsa Shmuk** began a careful restoration, uncovering stairwell wall paintings beneath layers of plaster, reviving the prewar façade’s sculptural depth, and reorganising the interior: seven apartments above, two shops below, a discreet elevator, and new systems seamlessly integrated into the old frame.

Today, **14 Levontin** once again reads as it was meant to: the loggia greets the street, the bay windows hold the rhythm, and commerce hums again beneath the arches. Behind this quiet symmetry, one can still hear it all — the ambition of the Sterlings, the pragmatism of Shaltiel, Wildenberg’s dispute, postwar decline, Cohen’s plea, and, finally, the cautious joy of renewal. The house has not merely survived; it has become a chronicle of the neighbourhood itself — a layered testament to a century of life in Tel Aviv.

You’ll walk through the very heart of old Tel Aviv — a neighbourhood where orange groves, missionary dreams, and the glow of early electricity all intertwined. The journey begins at the Model Farm and its iconic water tower, the birthplace of irrigation in Eretz Israel. From there, we’ll trace the footsteps of the Ishma’ilov family — Mashhadi *anusim* who built rental houses and inns for Persian merchants, yet lost much of their fortune under dramatic circumstances. We’ll pause in Gan HaHashmal, the city’s second public garden, which has witnessed the romance of the 1920s, decline, and the wave of 21st-century gentrification. The walk culminates at the grand Ohel Moed Synagogue — the “Tent of Meeting” — where eastern communities claimed their rightful place in the growing city. This is a journey through layers of time: from water to electricity, from merchant houses to gardens and synagogues — a story where every street guards a secret and every building speaks for its generation.