Places to visit in Atlanta

Atlanta: Georgia Aquarium & World of Coca-Cola — My Journey, August 21, 2025

Atlanta began as a modest railway stop — the end of the line that unexpectedly grew into the South’s busiest hub. The city was burned to the ground during the Civil War, yet out of the ashes rose a bold, industrious Atlanta. This is the birthplace of Coca-Cola, the cradle of the modern Civil Rights Movement, and home to the largest Black middle class in the United States. Few cities embody change and resilience the way Atlanta does.

At the heart of downtown lies Pemberton Place, a cultural crossroads where three icons stand side by side: the vast Georgia Aquarium, the playful World of Coca-Cola, and the moving Center for Civil and Human Rights. A short walk from the parking lot takes you past fountains and green lawns straight into this vibrant trio.

The Georgia Aquarium is breathtaking in scale — the largest in the Western Hemisphere. Its glass tunnel immerses you in the deep, as whale sharks and graceful manta rays glide overhead, surrounded by a dazzling cast of marine life. The highlight for many visitors is the dolphin presentation in the “Ocean Theater,” a show where science and spectacle merge to reveal the intelligence and energy of these remarkable animals.

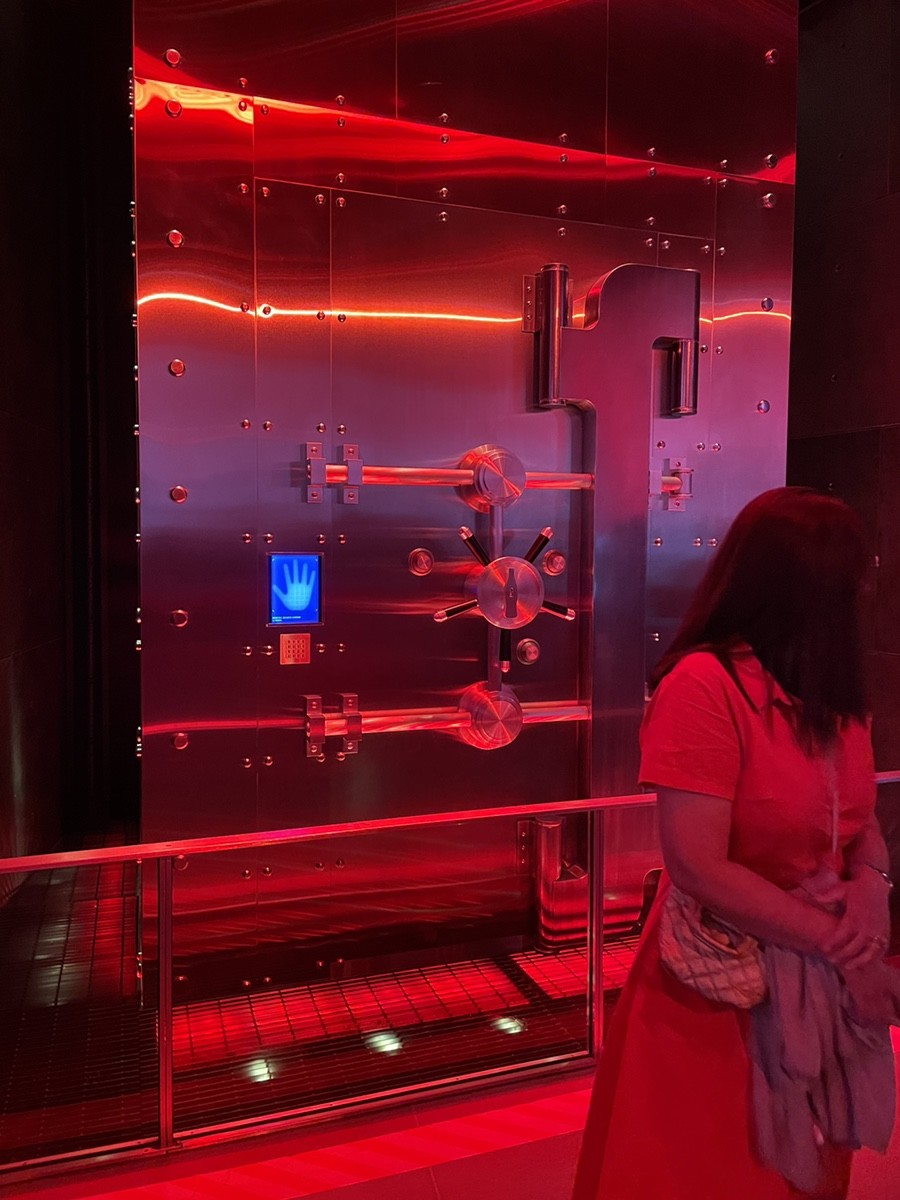

The World of Coca-Cola tells another side of Atlanta’s story. From Dr. John Pemberton’s original pharmacy syrup to a brand recognized by billions, the museum traces the evolution of a cultural icon. Visitors marvel at the legendary vault said to guard the secret formula, and the experience ends in the famous tasting room — more than 100 flavors from 40 countries. From familiar Fanta and Sprite to exotic drinks that spark delight or surprise, every sip is part of a global journey that began right here in Atlanta.

This covered walkway links the multi-level parking deck with Atlanta’s cultural heart — Pemberton Place. Along the way, signs point the direction: ticket counters to the left, the entrance to the Georgia Aquarium to the right. Digital boards display ticket prices and show schedules, so even the walk itself feels like the beginning of the experience.

Yet behind this practical design lies the city’s story. Atlanta was born in the 1830s as a rail junction called Terminus, named for the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Railroads made it the “Gateway to the South.” After being destroyed in the Civil War, the city rebuilt at astonishing speed, becoming an industrial hub and the face of the “New South.” In 1886, local pharmacist John Pemberton created the recipe for Coca-Cola here — a drink that would turn Atlanta into a global name.

Today, Pemberton Place brings together three icons that reflect Atlanta’s many identities. The Georgia Aquarium embodies both science and entertainment. The World of Coca-Cola showcases the ingenuity of a local invention that conquered the world. And the Center for Civil and Human Rights honors the city’s role as a cradle of the Civil Rights Movement and the birthplace of Martin Luther King Jr.

So the path from the parking lot into Pemberton Place is more than just a walk to the ticket booths. It feels like a symbolic gateway into Atlanta itself — a city where transportation, industry, and the struggle for equality all converge in one cultural landscape.

Stepping out of the covered walkway, visitors arrive at Pemberton Place, where the main entrance to the Georgia Aquarium dominates the square. Signs marked “Enter Here” and guiding barriers direct the flow toward ticket counters and security, keeping the process smooth and organized.

The aquarium is open daily from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM. General admission is about $54.99, while the flexible Anytime Admission is $67.99, and an annual membership runs around $110. Tickets for special shows — like the dolphin or sea lion presentations — cost about $15 extra. Buying tickets online in advance is strongly recommended, especially on weekends and holidays, to ensure entry at your preferred time.

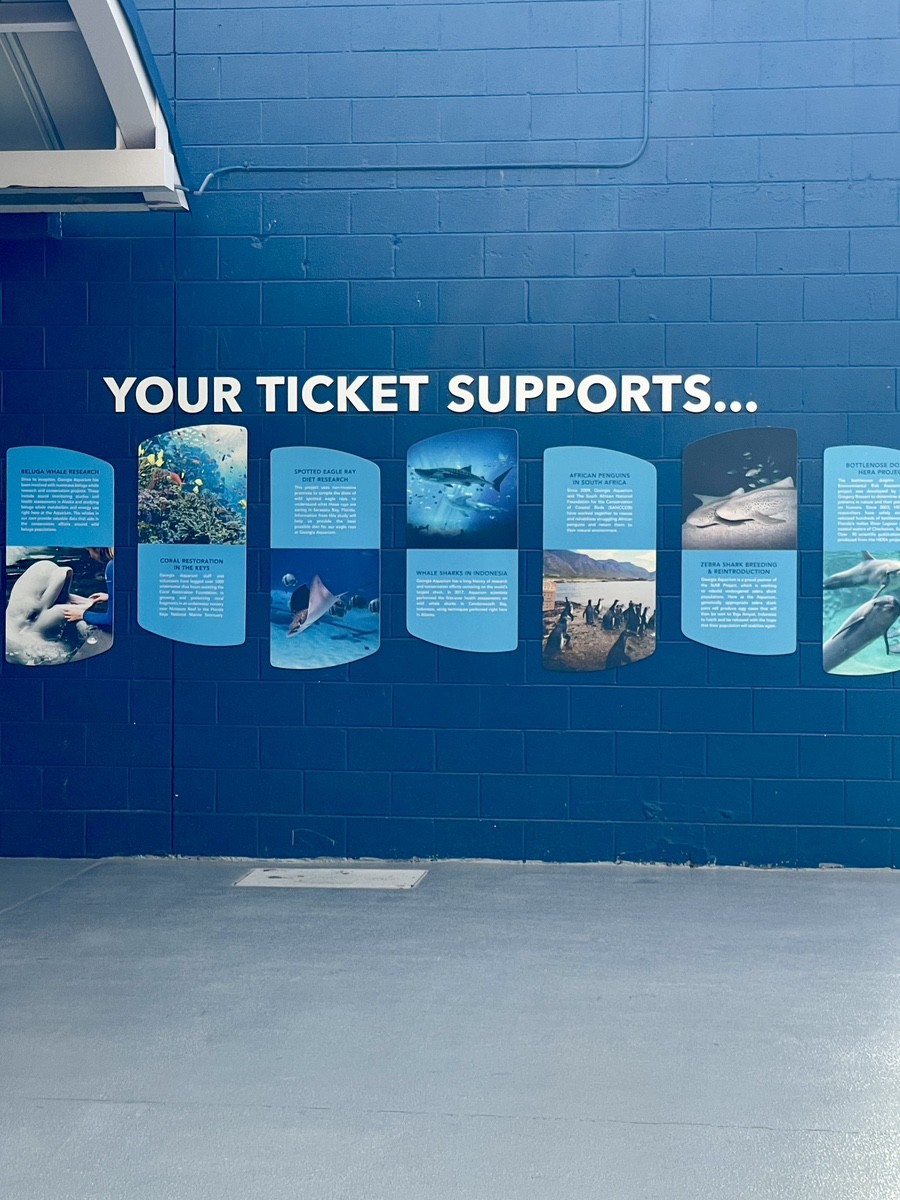

At the entrance, a striking blue wall carries the message “Your Ticket Supports…” — explaining how every purchase helps fund global conservation: coral reef restoration, beluga whale research in the Arctic, whale shark protection in Indonesia, and breeding programs for zebra sharks and African penguins. It’s a reminder that the aquarium is not just about entertainment but also about science and stewardship of the oceans.

Visiting the Georgia Aquarium is therefore more than a walk through underwater tunnels — it’s also a contribution to worldwide wildlife conservation. And the entrance zone at Pemberton Place feels like a grand lobby, setting the tone for one of Atlanta’s most celebrated cultural landmarks.

In the central atrium of the Georgia Aquarium, you feel less like you’ve entered a museum and more like you’ve stepped into a futuristic space terminal. The floor shimmers with ocean hues, soft blue lighting sets the mood, and signs guide visitors toward exhibits like Sharks!, Dolphin Coast, and River Scout, as well as cafés and theaters. From the very first steps, the design immerses you in a vast underwater world.

The aquarium opened in 2005, instantly becoming the largest in the world — a title it held until 2012 when newer facilities in Singapore and China surpassed it. Construction cost about $290 million, funded largely by Bernard Marcus, co-founder of Home Depot, who gifted it to the city for his 75th birthday. The building spans over 50,000 square meters and holds 10 million gallons of water — that’s more than 37 million liters.

The true stars of the aquarium are the whale sharks — the only place in the United States where you can see them. To house these gentle giants, engineers built a tank the size of a football field, with advanced filtration and current systems that replicate the open ocean.

Some fascinating facts: – Building the aquarium required 61 freight trains of equipment and materials. – Its custom filtration system processes millions of gallons of water daily. – The Cold Water Quest exhibit is home to beluga whales, brought here from facilities in Canada and Russia. – Wave and current simulators inside the tanks help fish maintain natural behaviors. – Ticket revenue supports not only operations but also global conservation programs, from coral restoration to saving penguins in South Africa.

More than just an attraction, the Georgia Aquarium has become a symbol of Atlanta’s transformation — a city once built on railroads and industry, now redefining itself through culture, education, and a commitment to protecting the natural world.

Inside the halls of the Georgia Aquarium, the ocean reveals itself in full. On the sandy floor rests a wobbegong shark, a flat-bodied predator patterned like the seabed. Perfectly camouflaged, it can wait motionless for hours, striking its prey in a split second.

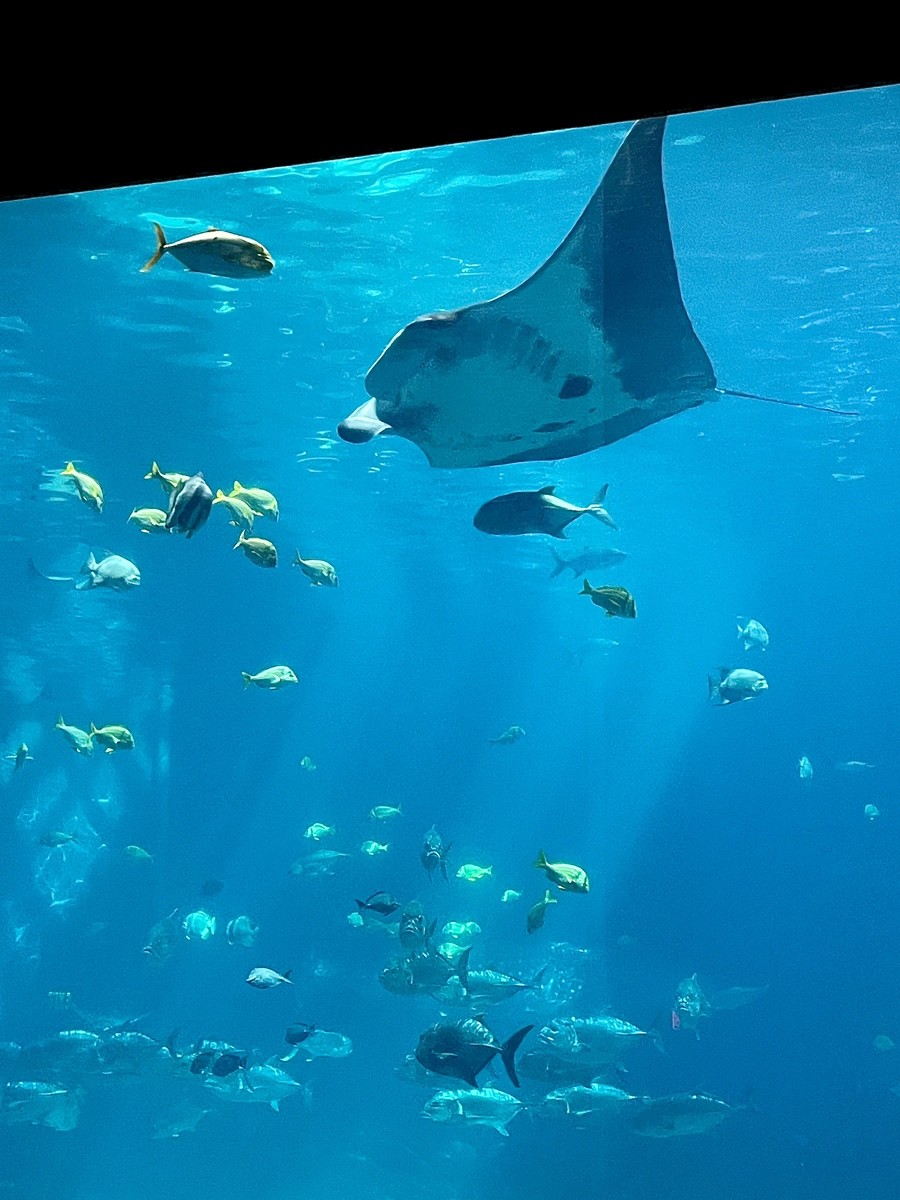

Above, a manta ray glides with effortless grace, its wings spanning up to 7 meters. Though immense, it feeds only on plankton. Researchers rank mantas among the most intelligent of fish — capable of memory, learning, and even recognizing themselves in mirrors.

Schools of tuna and jacks flash silver in the blue light. In the wild, tuna can reach speeds of nearly 70 km/h, but here they move calmly, giving visitors a rare close look at their streamlined power. Their presence adds energy and motion to the scene.

And then, the star of the aquarium: the whale shark. Stretching 12 to 14 meters long, it is the largest fish on Earth. Despite its size, it feeds only on plankton and tiny fish. To house these giants, engineers built a tank holding 24 million liters of water — the only place in the United States where whale sharks can be seen.

Walking through the transparent tunnel beneath the water, visitors find themselves surrounded: mantas soar overhead, tuna dart past, and a whale shark glides slowly by. For a moment, it feels as though you’ve stepped inside the ocean itself.

⸻

Quick fact cards:

🦈 Wobbegong Shark – Bottom-dwelling predator, expert in camouflage. – Lies in wait and strikes in an instant.

🌊 Manta Ray – Wingspan up to 7 m. – Plankton feeder, highly intelligent.

🐟 Tuna & Jacks – Fast schooling fish. – Can reach speeds of 70 km/h in the wild.

🐋 Whale Shark – Largest fish in the world (up to 14 m). – Gentle filter-feeder, harmless to humans.

The main tank of the Georgia Aquarium is not only home to whale sharks, manta rays, and thousands of fish — it’s also an engineering marvel. Its vast panoramic viewing window ranks among the largest in the world: roughly 18 meters wide, over 7 meters tall, and nearly 60 centimeters thick. Made from layered acrylic rather than glass, it can withstand the crushing force of millions of liters of water — a pressure equal to the weight of a skyscraper.

The acrylic panels were manufactured in Japan, shipped across the Pacific on special carriers, and then assembled in Atlanta. Several massive sections were fused seamlessly on-site, creating a single transparent wall. The joints are so fine they’re invisible, giving the illusion of staring straight into the open ocean.

Transporting the tank’s star residents — the whale sharks — was a global operation. They were flown from Taiwan in custom-built seawater containers, each monitored around the clock for oxygen, temperature, and water quality, with teams of veterinarians and marine biologists on board. Manta rays, far more sensitive to space and stress, were also carried in specially designed transport tanks.

The aquarium was envisioned from the start as a sanctuary for whale sharks, which had never before been displayed in the United States. To house them, engineers built a 24-million-liter reservoir, crowned by the giant viewing window that has since become an icon of the entire complex. Here, face-to-face with the largest fish on Earth, visitors experience the awe of the ocean brought to the heart of Atlanta.

For comparison: – Georgia Aquarium (Atlanta, USA) — window ~18 m wide, 7 m tall, acrylic thickness ~60 cm; the only aquarium in the U.S. with whale sharks. – Churaumi Aquarium (Okinawa, Japan) — “Kuroshio Sea” window ~22.5 m wide, 8.5 m tall, acrylic thickness ~60 cm; home to whale sharks in Asia.

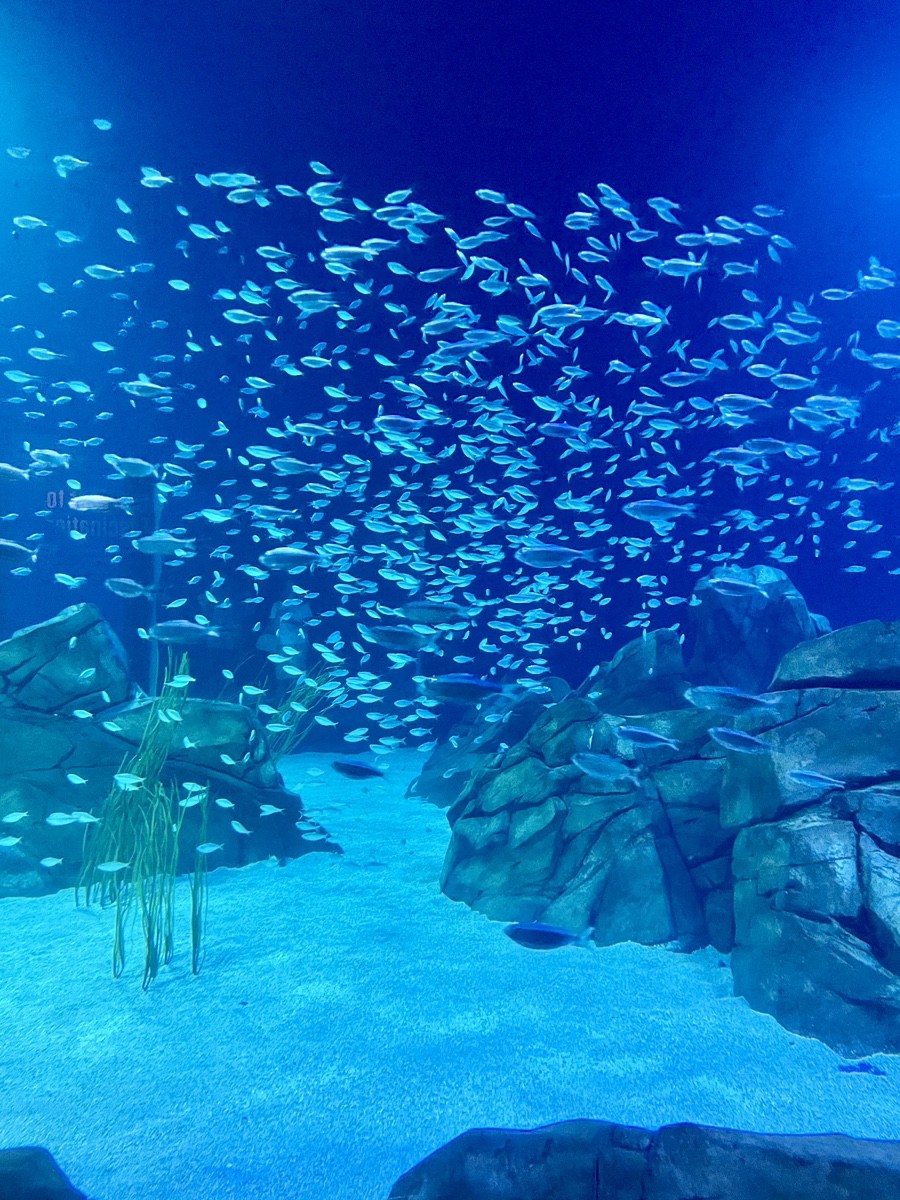

In front of the Georgia Aquarium’s massive viewing window, visitors witness a mesmerizing sight: a dense cloud of small silvery fish, the classic forage fish that form the base of the ocean’s food web. Moving as one, their synchronized turns create the illusion of a single living organism rather than thousands of individuals.

This survival strategy has been perfected over millions of years. By schooling tightly, each fish reduces its chance of being singled out. Predators are dazzled by flashes of silver, unable to focus on a target, and their attacks are scattered across the swarm. The response time is astonishing — within fractions of a second, the entire cloud shifts direction. The secret lies in the fishes’ lateral line, a sensory organ that detects tiny vibrations in the water, and in their wide-angle vision that keeps track of neighbors.

Normally, forage fish cruise at about 1–2 body lengths per second, but in a panic they can accelerate to 5–7 body lengths per second. To the human eye this looks like a sudden pulse through the school — a shockwave of motion that instantly reforms into a new shape.

In the wild, forage fish are the ocean’s most important resource, sustaining tunas racing at 70 km/h, powerful jacks and barracudas, diving seabirds, and entire pods of dolphins. Even in the aquarium, you occasionally see larger predators slice through the edges of the school, scattering the silver cloud before it fuses back together in seconds.

For humans, these fish are equally vital: commercial fleets harvest them with purse seines or lampara nets, often using lights at night to draw schools tighter before encircling them. In shallow waters, cast nets can capture them when the school brushes close to shore.

At the aquarium, biologists carefully manage the school with gentle currents and lighting, distributing food evenly to keep panic at bay. For visitors, it’s more than a dazzling display — it’s a lesson in ecology. These shimmering clouds of forage fish remind us that the ocean’s giants, from tuna to whales, ultimately depend on the smallest silver flashes in the sea.

This photo captures a classic coral reef scene, recreated inside the Georgia Aquarium. Each fish is like a living brushstroke, and together they paint the vibrant ecosystem of the tropics.

🟠 Anthias (Pseudanthias) – Small, orange-red fish that swirl in schools around the reef. – Native to the Indo-Pacific coral reefs. – Typically 5–10 cm long. – Fascinating fact: if the dominant male dies, one of the females changes sex and takes his place.

🔵 Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) — “Dory” – Bright blue with a black pattern and a yellow tail. – Common on Indo-Pacific reefs. – Grows up to 30 cm. – Grazes on algae, helping keep reefs healthy and clean.

🟡 Yellowtail Snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus) – Silver-gold body with a striking yellow tail. – Found in the Caribbean and Florida waters. – Can reach up to 80 cm in the wild, smaller in aquariums. – Travels in large schools, and is valued as a food fish.

⚫⚪ Moorish Idol (Zanclus cornutus) – Black-and-white with a golden stripe and a long trailing dorsal fin. – A reef icon of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. – About 23 cm in length. – Known as one of the most delicate reef fish to keep, feeding on sponges and tiny invertebrates in the wild.

🟣 Pufferfish (Arothron or Canthigaster species) – Rounded body, here seen in light violet and yellow tones. – Found in tropical coral reef zones. – Size ranges from 10 to 30 cm. – When threatened, they inflate into a ball; many species carry the potent toxin tetrodotoxin.

📌 Habitat All these species thrive in warm, tropical seas among coral reefs. The corals provide both shelter and food sources — from algae to plankton to small invertebrates. Their vivid colors serve not only as camouflage in the reef’s kaleidoscope but also as a way to signal and communicate with each other.

In front of the aquarium’s glowing blue wall, a slow-motion ballet unfolds — jellyfish drifting like beings from another world. Their fragile, transparent bodies look delicate, yet behind the beauty lies an ancient, brilliantly simple system for survival.

Jellyfish have no brain, no heart, no bones. Instead of a central control system, a web of nerve cells runs through the body, sensing light, reacting to water currents, and pulsing rhythmically to move forward. Nature found a way to build a creature without a command center — and it has worked for hundreds of millions of years.

Their tentacles may look like floating threads, but each one is armed with thousands of stinging cells. On contact, they fire microscopic harpoons loaded with venom. What’s astonishing is that this response doesn’t come from a brain — it’s triggered mechanically, as if the tissue itself decides to act.

Jellyfish are 95% water, yet thanks to a gelatinous substance called mesoglea, they hold their shape and glow in the aquarium lights like living lanterns. Even more remarkable — if cut apart, their tissues can regenerate, and sometimes fragments grow into entirely new individuals.

These creatures are older than the dinosaurs. They have survived every mass extinction that reshaped Earth. Perhaps their genius lies in simplicity: the fewest parts, yet maximum efficiency, a design refined by time itself.

This gallery is one of the true gems of the Georgia Aquarium — a hall entirely devoted to coral reefs. Through the massive viewing window, visitors step into a living city of corals, sponges, and anemones layered like towers and streets, each home to countless species playing their part in the ecosystem.

Hundreds of reef fish dart across the scene: bright schools shimmer like confetti, solitary guards patrol their territory, and delicate plankton feeders hover in the currents. It feels like a real ocean, alive with constant motion.

Though coral reefs cover just 0.1% of the ocean floor, they provide habitat for nearly a quarter of all marine species. At the Georgia Aquarium, this world is recreated with striking accuracy: water temperatures held at 25–27 °C, lighting that mimics the cycle of day and night, and systems that generate currents while maintaining delicate chemical balance.

⸻

🟡 Yellow Tang (Zebrasoma flavescens) – Iconic bright-yellow reef fish from Hawaii and the Pacific. Facts:

1. Can shift color — vivid yellow by day, pale at night.

2. Equipped with a sharp “scalpel” near the tail for defense.

3. Overfishing made it a symbol of reef conservation efforts in Hawaii.

🔵 Blue Tang (Paracanthurus hepatus) — the “Dory” fish – Blue body with black markings and a yellow tail. Facts:

1. When threatened, they play dead by lying on their side.

2. Juveniles are bright yellow before maturing into blue.

3. Live in symbiosis with reefs by grazing algae that would otherwise smother corals.

⚪⚫ Moorish Idol (Zanclus cornutus) – Striking black-and-white stripes with a long trailing fin. Facts:

1. Seen as a symbol of good luck in Hawaii, called mo‘o iwi.

2. Infamous among aquarists — rarely lives long in captivity.

3. Specializes in eating sponges, a tough diet few reef fish can handle.

🐟 Yellowtail Snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus) – Silver body streaked with a golden line and bright yellow tail. Facts:

1. Migrate long distances to gather for mass spawning events.

2. A key commercial species across the Caribbean.

⸻

In the middle of Atlanta, this recreated coral reef is a reminder of the ocean’s fragile beauty — and of the extraordinary diversity that thrives in just a sliver of the sea.

One of the most popular venues at the Georgia Aquarium is the Dolphin Coast Theater, a 1,800-seat arena with a massive screen and a pool more than seven meters deep. Here, bottlenose dolphins perform not circus tricks, but natural behaviors: synchronized leaps, swift turns, and the acoustic signals they use to communicate in the wild.

Highlights of the theater: – Designed so visitors can see dolphins both above the water and through transparent walls below the surface. – The pool is continuously filtered, oxygenated, and kept at 24–26 °C, replicating natural conditions. – Each dolphin receives individualized veterinary care and diet plans; training relies exclusively on positive reinforcement.

Why this isn’t a circus show: – In circuses, animals are forced into unnatural tricks for spectacle. At the aquarium, dolphins showcase behaviors they naturally use in the ocean — leaping, swimming in synchrony, and communicating with clicks and whistles. – Each program is educational, explaining dolphin biology, social behavior, and the environmental threats they face. – Georgia Aquarium supports conservation efforts for wild bottlenose dolphins, funds research, and uses these presentations to inspire awareness of marine mammal protection.

The dolphins here are bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), the most widespread dolphin species on Earth. Their name comes from Greek delphis (“wombed fish,” an ancient term for dolphin) and Latin truncatus (“shortened snout”). In the wild, they live in pods of dozens, sometimes forming super-groups, and hunt fish and squid using echolocation.

At the Georgia Aquarium, these dolphins serve as ambassadors — a living bridge between the marine world and the human audience, reminding visitors that behind every leap is both beauty and science in action.

Downtown Atlanta begins at Pemberton Place, the gateway to what many call the city’s Cultural Mile. Here, within a short walk, you’ll find four of Atlanta’s most iconic attractions:

📍 1. Georgia Aquarium The largest aquarium in the Western Hemisphere, home to whale sharks, manta rays, dolphins, and thousands of marine species. Don’t miss the panoramic underwater tunnels and the dolphin theater.

📍 2. World of Coca-Cola An interactive museum dedicated to the world’s most famous soft drink. Discover the company’s history since 1886, peek at the legendary “secret formula,” and sample more than 100 flavors from across the globe.

📍 3. Centennial Olympic Park Built for the 1996 Olympic Games, this park is now the green heart of downtown. Its Olympic-ring fountains, lawns, and performance spaces host concerts, festivals, and are perfect for a break between museum visits.

📍 4. CNN Center Headquarters of the global news network. A guided tour takes you behind the scenes, into studios and control rooms, to see how international news is produced and broadcast.

Together, these landmarks create a walkable cultural corridor — a compact journey through Atlanta’s marine wonders, industrial heritage, Olympic spirit, and media power.

The World of Coca-Cola in Atlanta is more than a museum — it’s a full multimedia experience celebrating one of the world’s most iconic brands. Inside you’ll find vintage vending machines (like the ones in your photos), historic posters, collectible bottles, and branded memorabilia dating back to the late 19th century. The attraction is divided into themed zones: the history of the brand and its creators, a gallery of retro machines, a theater showing a short film on the “magic of Coca-Cola,” the legendary Vault of the Secret Formula, and of course, the tasting room where visitors can sample dozens of Coca-Cola products from around the globe.

Visitor essentials: The museum is located next to the Georgia Aquarium and Centennial Olympic Park, making it easy to combine in one trip. Tickets cost about $20–25 for adults and are best purchased online to skip the lines. Plan for 2–3 hours to explore comfortably. Photography and video are welcome throughout. The most popular highlight is the tasting room — where you can try unusual flavors like Italy’s bitter Beverly or fruity sodas from India. Before leaving, many visitors stop at the gift shop, which offers limited-edition bottles and retro souvenirs you won’t find anywhere else.

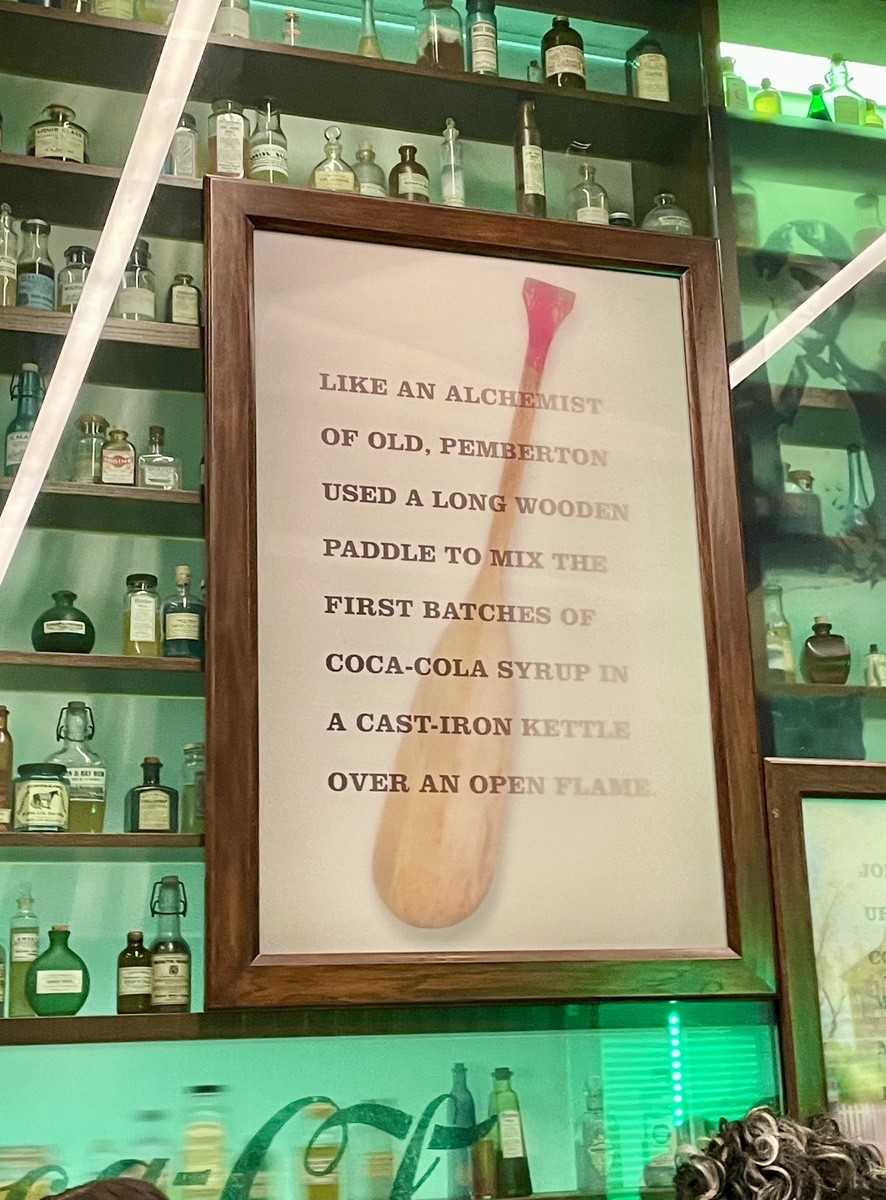

The story of Coca-Cola begins in Atlanta, where pharmacist John Pemberton, like a modern-day alchemist, stirred his first batches of syrup in a cast-iron kettle over an open flame in the late 19th century. The drink quickly caught on at soda fountains, served by “soda jerks” who mixed carbonated water with syrup using a lever. Even in those early days, advertisements highlighted that Coca-Cola contained no artificial flavors or preservatives.

The rights to the formula soon passed to entrepreneur Asa Candler, who purchased it in the 1890s for just $2,300. Syrup was shipped in distinctive red-painted barrels, making the brand instantly recognizable. Candler fiercely guarded the secret recipe: he personally ordered ingredients, locked the formula in a safe, and kept the only key. As sales grew, early advertising warned against imitations, promoting Coca-Cola as “the real thing.”

By 1919, the Candler family sold the company to a group of Atlanta investors for $25 million, one of the largest business deals of its time. For several years, the formula itself was moved to a New York bank vault. Meanwhile, bottling transformed Coca-Cola into a drink available anytime, anywhere, not just at soda fountains.

A major breakthrough came in 1916 with the introduction of the famous contour bottle — designed to fit perfectly in the hand, instantly recognizable even in the dark, and impossible to confuse with anything else. Alongside it grew myths, such as the rumor that Coca-Cola was once green, a story that only fueled the brand’s mystique.

From Pemberton’s kettle to Candler’s red barrels to millions of bottles worldwide, Coca-Cola evolved from a pharmacy syrup into a global symbol — The Real Thing — a taste that cannot be mistaken for anything else.

One of the highlights of the World of Coca-Cola in Atlanta is the high-security vault said to protect the brand’s most valuable treasure — the secret formula created by John Pemberton in 1886. For decades the recipe was guarded by Asa Candler and his successors, locked away in safes and transferred between banks. Since 2011, the company has turned this mystery into an exhibition: visitors walk through dramatic halls to a vault where the “secret” is symbolically kept. Whether myth or reality, the ritual of secrecy has become part of the brand’s magic.

The story of Coca-Cola’s guarded formula has an ironic parallel in the history of Lagidze’s drinks in Georgia (the country, not the U.S. state). In the late 19th century, pharmacist Mitrofan Lagidze invented syrups made from natural fruit and herbs — lemon, tarragon, quince, pear. They became a beloved part of Georgian and Soviet culture. Yet unlike Coca-Cola, Lagidze’s brand never turned into a global empire. With revolutions, wars, and shifting economies, the drinks remained a local specialty, cherished but never exported widely.

Together, these two stories reveal how differently fate can treat inventions born in the same era. Coca-Cola, shielded by myth and marketing genius, became a universal icon. Lagidze’s drinks, equally authentic and natural, stayed tied to their homeland. And so, in Atlanta, standing before the Coca-Cola vault, visitors are reminded that global fame depends not only on flavor — but also on timing, history, and the power of storytelling.

They say there’s a place in Atlanta where time seems to pause, fizzing softly in your glass. This is the tasting room of the World of Coca-Cola — a hall where flavors from every corner of the globe gather like travelers in a bustling marketplace. Some feel like old friends — lemon Sprite, Cherry Coke, tropical Fanta — while others are rare visitors you won’t find anywhere else.

Here you can pour a hundred drinks if you like: more than 100 flavors from 40 countries await. Coca-Cola today owns nearly 500 brands, produced at over 900 plants worldwide, employing around 700,000 people. Every second, about 19,000 servings of Coca-Cola are consumed — and in Atlanta, it all begins with a single sip.

The unusual flavors are like a gallery of stories: Peru’s Inca Kola, tasting of bubblegum; Thailand’s green Fanta Melon Frosty; Mexico’s Lift Manzana, with its crisp apple bite; and Africa’s fiery Stoney Tangawizi, a ginger soda with real heat. Then there’s Italy’s infamous Beverly, bitter like an aperitif and widely considered the “worst soda in the world.” Travelers argue over which is best, but agree on one thing — no visit ends without at least one wince from Beverly.

Whispers say Atlanta is also where secret recipes are born: a peach Coke carrying the fragrance of Southern orchards, or a raspberry version as sweet as summer on a market square. While the world drinks its familiar cola, Atlanta keeps its heart in these bubbles — a quiet music of history, sparkling in every glass.